1. Lebovitz and Warhol and a Case of Withering Sights

2. Pointing and Shooting in George Plimpton's Apartment

3. When Irving Got Mad. And Vice Versa.

4. Misshapen Chaos (my Juliet adventure)

5. Joe Franklin: Venerable. Inimitable. Flammable.

6. A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Marquee

7. A Radio Flyer in an Empty Nest

8. By the Way, We Even Called Him Satchmo

9. Love Between the Covers

10.The story of a water-breaking app

11. The non driverless car of the future

12. The best inning of a football game

13. Pot luck in Colorado

... look at the bottom of this page for information on all my books

_________________________________

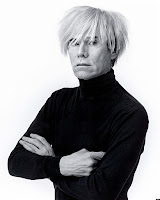

1. Lebovitz and Warhol

and a Case of Withering Sights.

Peter

Lebovitz and I were sitting in the company cafeteria. I can’t recall exactly

how the topic came about, but after the second or third bite of a turkey wrap, Peter—the

other token Jew in our little group—told

me that when he was nineteen years old he appeared as a minister in an Andy

Warhol film. I stopped chewing at that point, not because of the wrap itself

(which wasn’t bad, actually), but because I was having a little trouble

picturing a guy I had always thought of as a cross between Alex Reiger in “Taxi”

and Dr. Sidney Friedman in “M*A*S*H” (with a dash of Mark Twain thrown in) as a

minister in an Andy Warhol movie.

I’m sure there were a lot of different kinds of people who appeared in Warhol films in the 1960s, but I doubt that a Peter Lebovitz type—which is to say a Judd Hirsh/Allan Arbus/Samuel Clemens type—was ever one of them. After all, didn’t Peter’s revelation mean that he participated in a crazy approximation of a motion picture production directed by the eccentric Warhol? Didn’t the revelation mean that Peter was surrounded by a phalanx of drugged-out, sexed-up, weirdo Warhol sycophants in a paint-splattered den of vice somewhere in lower Manhattan?

I’m sure there were a lot of different kinds of people who appeared in Warhol films in the 1960s, but I doubt that a Peter Lebovitz type—which is to say a Judd Hirsh/Allan Arbus/Samuel Clemens type—was ever one of them. After all, didn’t Peter’s revelation mean that he participated in a crazy approximation of a motion picture production directed by the eccentric Warhol? Didn’t the revelation mean that Peter was surrounded by a phalanx of drugged-out, sexed-up, weirdo Warhol sycophants in a paint-splattered den of vice somewhere in lower Manhattan?

|

Not my Peter Lebovitz!

Peter and I

worked at a large German-owned manufacturing company in northern New Jersey. I

handled employee communications, Peter was a marketing executive. As part of my

job, I was required to tap into executives like Peter for employee newsletter

stories and other internal communications projects, and sometimes executives

like Peter had to tap into me for grammatical help or to explain why the proper

phrase is “I couldn’t care less.” Peter

and I didn’t socialize outside of the building, but inside we made the most of

whatever a platonic on-site work relationship can be. For instance, we both

played the Jewish thing to the hilt whenever we saw each other in the

hallways—sprinkling Yiddish words and phrases into our conversations as a sort

of cynical fraternal code within the walls of our company which, in a much

earlier manifestation, was part of a German conglomerate that allegedly did

business with the Nazi party. Other than that secret code, there wasn’t much

else to the relationship.

But then

came that turkey wrap exchange. That brought the friendship to an entirely new

level. Unfortunately, it was a level in which Peter had very little interest.

As far as imagining

Peter in a Warhol movie was concerned—or not being able to picture it in the

first place—I knew right off the bat that I might be alone in my appraisal,

simply because not many people see, or have seen, Andy Warhol movies. Most Warhol

films are warehoused, awaiting preservation, and most are a challenge to watch.

Like the one that shows a guy sleeping for five-and-a-half hours.

|

| Peter Lebovitz |

It wasn’t

easy.

Other than getting

him to share with me the most basic recollection of his involvement, it was

more difficult to get Peter to discuss the story than it was to stay awake

through tedious CIP and ISO meetings. Several times after he spilled his Warhol

beans I told him that I was fascinated by his disclosure and wanted to write a

story about it. But Peter kept telling me that to him the entire experience was

“Just one long day spent with a total fake, although a famous total fake. It wasn’t filmmaking,” he said about the

artist’s cinematic efforts, “it was just filming. There’s a difference.” I said

that Warhol in general was a fascinating cultural footnote (the artist died

from a heart attack in 1987 following gall bladder surgery), and that he,

Peter, should be proud to have been a part of that footnote. Peter responded that

the entire incident was “drek.” I

mentioned that if any article I would end up writing was published in a major

magazine, he, too, could become an intriguing footnote—at least for the amount

of time it would take for someone to read the article. Peter replied to that

with an indifferent “Oy.” I said that

at the very least, it must have been an interesting afternoon that he’ll

remember forever—an afternoon filled with degenerate craziness and decadent

shenanigans. But Peter said that at the very most it was a boring, annoying, and

infuriatingly long day that he wishes he wouldn’t have wasted.

This

journalistic goal of mine began in 2003, which was also the year that my

department at the company was eliminated. Suddenly I was unemployed. But I used

the shocker of my termination as an incentive to jump into this project. After

all, I started out as a trade magazine writer and reporter and had always

believed that I’d find my own Watergate one day. But it was a rocky start with Peter because the only three things that he was able to tell me about the Warhol movie

was that it was shot in 1966, that it was filmed in someone’s Manhattan

apartment, and that it was some kind of take-off on a famous book from long ago.

He couldn’t even remember the name of the damned film.

I went into

research mode. Before long, I came upon a brief reference to a Warhol production

called “Withering Sights”—a tease on the title and story of “Wuthering

Heights,” the 1847 Gothic novel by Emily Bronte.

My first

call was to Greg Pierce, a film and video technician at the Andy Warhol Museum

in Pittsburgh. Greg didn’t know much about that particular film, but he did

give me the name of Callie Angell, who was curator of the Andy Warhol Film

Project at the Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan and a consultant to

the Museum of Modern Art on the preservation of the Warhol films. (Callie’s

father was the noted writer and New Yorker Magazine senior editor Roger Angell,

whose mother was married to E.B. White, author of “Charlotte’s Web” and “Stuart

Little.”) Callie confirmed for me that a motion picture called “Withering

Sights” was indeed shot on February 26, 1966. Bingo. I found Peter’s film. It

didn’t make me Woodward-Bernstein (or, more appropriately, just Bernstein), but

it was a start, and it felt good.

Peter couldn’t

care less.

*

Nineteen

sixty six. I was only nine at the time. But my cafeteria colleague was already

working. He was, in his words, “doing a menial job in a market research

company, along with other misfits from the fringes of society. Market

research,” Peter theorized, “attracted the intelligent dregs of society, like

out-of-work actors and head-in-the-cloud writers.”

Peter was

neither, but one of his coworkers was. Richard Schmidt, who wanted to be an actor,

was a regular visitor to the Factory, the Manhattan studio on East 57th

Street where Warhol and his hangers-on made music, movies, mayhem, and

sometimes even a little art. One day Schmidt invited Peter to go along with him

to the Dakota apartment complex on West 72nd Street and Central Park

West. Warhol and his merry pranksters were making a film there, Schmidt said,

and Peter was given the opportunity to play the small part of a minister.

“So a

couple of us piled into a taxi and drove to the Dakota,” Peter recalls. “We

were herded into a magnificent apartment. There was a camera there, tripods,

lights… I was told to stand in front of a young couple to be married and say,

‘Now you are man and wife. Kiss and be wed.’ I noticed that the other actors

were ad-libbing, and no one appeared to be taking anything very seriously.

Plus, a bunch of us were fed up with sitting around all day. So, instead of

‘Kiss and be wed,’ I said, ‘Kiss and be cursed.’ And then, while the camera was

still rolling, someone off to the side called out, ‘Curse you all.’”

That’s

where Peter wanted to end the story. But I wanted more. A lot more. I wanted to

learn about the disposition of the hangers-on, their attitudes, how many drugs

were being used, how much sex was going on...

“Drugs? I

don’t think there was a single drug there,” Peter said. “As a matter of fact, I

seem to recall that Warhol was determined not to have anything like that around

at all.” (That may have been true on the

“Withering Sights” film set, but there are several reports of drug use by

members of Warhol’s Factory crowd over the years.)

At my

urging, Callie Angell at the Whitney looked up her notes on “Withering Sights.”

In her role as curator of the Warhol film project at the museum she had once

viewed the original camera negative, difficult as that can be to watch, before

it went into storage to await preservation. Callie noticed that she had added a

parenthetical insert to her notes while writing about the wedding scene:

“A

priest comes in (who’s this?) and marries them over the dead body on the

floor.”

I visited

Callie at her office on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. She showed me the “who’s

this?” notation she had made about the priest, and let me peruse various books

and papers she had about Warhol and his film activities, none of which shed any

additional light on “Withering Sights.” Nor did she have any photographs from the

production, or the script. No one seemed to have the script. She confirmed that

the film itself was locked away in a Museum of Modern Art storage facility

somewhere in Pennsylvania.

I next

spoke with Kitty Cleary, who worked in the film and video library at the Museum

of Modern Art, which had a Warhol film preservation project in the works. But

Kitty merely confirmed that there was just one camera negative original of

“Withering Sights,” and that it was almost certain that getting permission to

view it would be impossible because of the delicate nature of film

preservation.

I checked with

Steven Higgins, at that time curator of MOMA’s film department, and was told

the same story that Cleary told me.

While all

this was going on, I kept Peter apprised of my efforts. At one point he said to

me, “My wife thinks we’re both nuts. Especially you.”

*

With a

little more research I discovered that “Withering Sights” was penned for Andy

Warhol by Ronald Tavel, a writer who had met the artist in late 1964. Warhol had

just purchased a sound camera and had shot his first sound film. One of the earliest

collaborations between Warhol and Tavel was called “Vinyl,” based on the novel

“A Clockwork Orange” by Anthony Burgess. Clearly bitten by the cinematic bug, throughout

1965 Warhol and his Factory crew amassed quite a number of full-length unedited

reels—many of them long, static shots of one subject or another. He financed

these productions with the money he earned from his artwork. Between 1963 and

1968 he produced hundreds of movies, including approximately 500 three-minute

personality portraits (the famous “Screen Tests” project), and another

hundred-plus features. Collectively it provided a peek into the underground culture,

a pinch of Hollywood dream weaving, some documentary filmmaking (whether intentionally

or otherwise), a little pornography, and some performance art before that was

even fashionable.

According

to Tavel, who I had finally located via email in 2008, Warhol at one time had

told him that his two favorite novels were “Wuthering Heights” by Emily Bronte

and “Jane Eyre” by Emily’s sister Charlotte. But Tavel never believed that

Warhol actually read either of the Bronte books; more likely he was referring

to the Hollywood movie versions because he talked of the books in terms of the

actors who played key roles in the films, such as Laurence Olivier and Merle

Oberon in “Wuthering Heights” and Orson Welles and Joan Fontaine in “Jane

Eyre.”

Tavel also

told me that he had wanted Edie Sedgwick, a socialite and current Warhol

superstar, to play the key role of Catherine Earnshaw in the film. But the part

went to Ingrid Von Scheven, who lived in New Jersey and worked as an office

temp in Manhattan. Why? As the story goes, Von Scheven was spotted at a bar on

42nd Street and recruited to be in the Warhol troupe as a way of

punishing Sedgwick who, it was said, had become difficult to work with. Von

Scheven eventually adopted—or was given—the name Ingrid Superstar, likely as a

ploy designed to further annoy Sedgwick. Ten years later, in December 1986,

Ingrid left her apartment to buy some cigarettes and was never heard from

again.

Heathcliff in

“Withering Sights” was played by Charles Aberg, who had also taken part in

Warhol’s “Screen Test” project. By many accounts, Aberg was apprehensive and

ill at ease throughout that entire shooting of the Bronte takeoff.

The role of

the minister went to that 19-year-old Jewish market researcher who earlier that

morning had no idea he’d be appearing in an Andy Warhol film.

Shot in

black & white, the 70-minute “Withering Sights” was filmed in the Dakota

apartment of Panna Grady, a patron of the arts whose suite was somewhat smaller

than Tavel had hoped for, considering that several scenes required the use of

many people as part of the sprawling, festive atmosphere that the screenplay

called for. Tavel remembers that on the day of the shoot, Grady’s suite was

overflowing with “extra extras, fashion editors, guests, and morbid curiosity-seekers

who caused a delay in rolling Reel One.”

Peter was

more than just an ‘extra extra.’ He was a character with scripted lines (only

two—but lines nonetheless) and, as Peter had recalled, he ad-libbed an

additional few words, even though he probably didn’t even know what ‘ad-lib’

meant at the time. It was only after I had piqued Tavel’s interest in my Peter

odyssey that he sent me, via email, a pdf of the screenplay (which has since

been made available on line; on the screenplay, the title of the film is listed

as “Heathcliff, or, Withering Sights”). It includes a 2,700-word introduction

that Tavel wrote about his role in the project, with a focus on his complex

professional relationship with Warhol. I downloaded the screenplay and told

Peter about it. He couldn’t believe I had it. Maybe he just didn’t want to.

In the

screenplay, near the end of Reel One, Catherine Earnshaw meets up with Edgar

Linton, takes his arm and moves with him toward a minister. Church music

begins. Then:

MINISTER: Do you, Catherine Earnshaw of

Withering Sights, take this weakling, Edgar Linton of Thrushcross Grange, as

your lawful wedded spouse?

CATHERINE: Spouse? Sounds like mouse. Sounds

ominous. Sounds dirty, too.

MINISTER: Then kiss and be coupled.

CATHERINE: Oh, I’m so excited! My very own

wedding day.

EDGAR: And my very own wedding night!

HEATHCLIFF: Curse you both!

The

Minister appears no more. That was the end of Peter’s film career—but not the

end of my journalistic involvement in the film. I tried to convince Peter that

I was doing a good job of making something out of what he defiantly continued

to say was nothing (i.e. drek), and

that I should pursue the odyssey even further. After all, didn’t I identify the film, learn

a little about its production, and find a reference to the real Peter Lebovitz on

paper (Callie’s parenthetical inquiry as to the identity of the minister)?

What’s more, I was now able to measure Peter’s recollection of the shoot against

the actual shooting script. And it only took five years! So I set out to

determine whether or not “Withering Sights” had any life beyond its filming in

Panna Grady’s apartment (and its brief mention at a lunch table in New Jersey).

Other than Callie Angell once viewing the original camera negative and, more

recently, Greg Pierce at the Warhol Museum looking it over with a

photographer’s loupe, the answer to that question seems to be no, it had no

other life, publicly or otherwise.

Late in

1966, Warhol announced a 25-hour film project that was to be comprised of

several self-contained features, collectively called “****” (pronounced as

“Four Stars”), the final version of which was to have more than 90 full-length

reels to be shown just once (on two projectors in a single superimposed image)

at the New Cinema Playhouse in New York. It was once rumored that the 70-minute

“Withering Sights” was to have been one of the self-contained features in

“****.” But according to Pierce, that didn’t happen. “****” was shown from 8:30

p.m. on December 15, 1967, to 9:30 p.m. the following day, but Peter Lebovitz’s

short wedding scene was never seen because “Withering Sights” itself was never seen.

Tavel, too,

saw neither “****” nor “Withering Sights.” He was far more dedicated to his

theater work at the time to worry about Warhol films. (Two of his one-act plays

had been performed at the Coda Gallery in downtown Manhattan). I tried to contact Tavel once more to discuss

the matter further, but discovered that he had passed away in March 2009. He

had been midflight between Berlin, where he was working on a film festival, and

his home in Bangkok. He was 73. In hopes of having another discussion with

Callie Angell, whose work in the field of Warhol scholarship has often been

called unparalleled, I attempted to contact her, but she, too, had passed away.

Her body was found May 5, 2010 in her apartment, an apparent suicide.

Certainly I

would love to be able to see the film myself (impossible right now), but I would

also love to find some written or recorded reactions to the filming of “Withering

Sights” from someone who was involved in the production. Other than Callie

Angell’s few notes, however, there seems to be nothing like that at all in

existence, and with both her and Tavel gone, the chance for more is dimmer than

ever. A book called “The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol,”

by J.J. Murphy, was published in April 2012 by the University of California

Press, but there is no mention in it of “Withering Sights.” The Huffington Post

ran a piece in August 2012 called “17 Andy Warhol Films You Probably Haven’t

Heard of But Should Know.” It mentions “Sleep” (1963), “Mario Banana 1” (1964),

“Vinyl” (1965), “Blow Job” (1966), “The Nude Restaurant” (1967), and twelve

others—but not “Withering Sights.” The Bronte takeoff lives somewhere in the black hole of Warhol

filmdom.

There is, however, a light hovering high up over

that black hole. “We are in the process of digitizing every inch of the Andy

Warhol film catalog, whether they’re from camera originals or prints,” the

museum’s Greg Pierce told me in September 2015. “We’ve finished batch one,

we’re starting on batch two, and batch three will include ‘Withering Sights,’”

he reports, encouragingly. But when asked to guess when the movie will finally

be available for viewing, his response is somewhat less encouraging: “It’s

years down the line,” he admits. “Years!”

In the

past, a lack of funding was blamed for an inability to preserve the Warhol

catalog. But with the project now on track, there’s hope that everyone (everyone

who wants to, at least) will one day be able to see it, either at the museum in

Pittsburgh or, because of digital’s growing capabilities (especially in a few

years), virtually anywhere. Even Peter can see it. Although he probably won’t

want to.

His complete

lack of curiosity is curious, though his persistence in calling me a fool to

continue my journalistic quest is refreshing. When other people call me a fool,

it hurts; when Peter does it, it’s with such tranquility, such affability, that

it’s almost inspiring. Maybe playing a minister had an effect on him that he’ll

never truly acknowledge. Maybe that’s

what my pursuit has accomplished.

But it also

accomplished this: before I got involved, no one in the world of Warhol

scholarship had ever heard of Peter Lebovitz. After speaking with Callie Angell

at the Whitney Museum, who was always working on updating the Warhol film

catalog, Peter’s name may now officially be logged in—somewhere—as a performer

in “Withering Sights.” I say that counts as a big accomplishment. Peter says

it’s practically insignificant.

Thinking of

Callie reminds me of one question that still haunts: as the only one I had

talked to who actually had viewed all 70 minutes of the camera negative, she

recalled that the minister married the couple over a dead body on the floor.

But Peter has no recollection of a dead body at all. (The screenplay doesn’t specify

one, either.) Also, Peter says that the off-screen voice that calls out “Curse

you both” was an ad-libbed reaction to his own ad-libbed “Kiss and be cursed,”

although the screenplay indicates that “Curse you both” was actually written

into the script. In one final attempt to make something out of nothing, I

grilled Peter about these two critical discrepancies. After all, despite the

fact that Warhol kept his set drug free, it was

1966, and Peter was a young ‘dreg of

society’ (his words, not mine) in the urban jungle. So I asked him if there was

something he wanted to tell me about his state of mind during the filming in

that Central Park West apartment. He thought about it for a moment and had a

very engaging response:

“As Timothy

Leary said, if you remember the 60s, you weren’t there.”

Ambiguous,

but engaging.

Recently

Peter had one final comment before deciding to irrevocably close the door on

this chapter of his past. He told me that my ridiculous persistence over the

last decade has turned his quarter-hour of notoriety into the longest, most annoying

15 minutes of fame.

That famous phrase, which Peter adopted so freely, would not have been his to adopt if not for Andy Warhol.

The End

The End

2. Pointing and Shooting in George Plimpton’s Apartment

I

was at the library the other day and came across the oral biography called

“George, Being George.” It contains many wonderful recollections by notable

people on their encounters with the writer George Plimpton. I’ve never been

notable enough to have been asked to contribute, but I do have my own ‘George

being George’ story. I don't know if Mr. Plimpton, who passed away in 2003,

would have wanted me to tell it. But I’ll tell it anyway, because it has long

been my goal to tell interesting stories about colorful people—just like he did.

Of course, he did it about people who were still alive. I probably wouldn’t

have been brave enough.

He was brave. And

very colorful.

Back

in the days when there were just seven channels to watch, and taping shows to view

later on was not yet possible for most families, television specials were a hotly

anticipated commodity. At least in my

childhood they were. As a kid I always looked forward to the George Plimpton

specials that aired every once in a while, and made sure never to miss a single

one. I enjoyed the ‘professional amateur’ stunts for which he was famous:

George the standup comic, George the trapeze artist, George the football

player... George Plimpton entertained and, in turn, educated us simply by

trying things he was genuinely interested in, yet could accomplish with only

moderate success. I admired his conviction, his love of adventure, his sense of

humor, his singularity of character and style. As a novice writer with plenty

of professional dreams of my own, I imagined myself a George Plimpton of the

Twenty-First Century.

But

back in 1987. I was just a twenty-something public relations manager for the

Olympus camera company on Long Island. I kept up the dream—but also worked hard

in public relations to pay the bills and support my new and growing family. One

of my functions at Olympus was to come up with ideas for new product press

conferences. I always tried to do something a little newsworthy—like create a

publicity stunt, or bring in a celebrity. A new product we were introducing that

fall was a point-and-shoot camera designed to make amateur photographers feel

like professionals, so the first person I thought of was George Plimpton, the

professional amateur. I looked him up in the Manhattan phone book. He was

listed! I called. He answered.

Nervously,

I explained my idea to him: first I would make a few introductory remarks,

briefly mention the product’s market position as an amateur’s professional

camera, then introduce him. At that point he would share with the audience a

few of his ‘professional amateur’ stories, and wrap it up by describing the

camera’s remarkable features and capabilities.

To

my surprise and delight, Mr. Plimpton agreed on the spot to do the press

conference for Olympus. We decided to meet at his apartment on the Upper East

Side the following week to go over the details and discuss some additional

particulars.

On

the day of the meeting, I was nervous and excited. I was about to meet the

famous, wild and erudite professional amateur whom I had enjoyed on TV specials

so many times, the man who was so winningly portrayed by a pre-“M*A*S*H” Alan

Alda in “Paper Lion,” the 1968 a feature film about Plimpton’s stint as a

Detroit Lions quarterback that had always been one of my favorite movies.

At

Mr. Plimpton’s apartment, a young assistant ushered me into what looked to be a

combination living room and office. For a moment I felt as if I was the one in a movie: a young,

inexperienced PR guy—and fledgling novelist and playwright—standing in the home

of an older and very successful writer and editor, and silently praying that,

in some way, he might be able to boost a fledgling career. I’m pretty sure that

the room in which I was standing was where Mr. Plimpton did much of his writing

and editing, perhaps even for the Paris Review, which even then I had looked

upon as a byline goal for my still-nonexistent writing career. I imagined it

was the room where he kept many important papers and books and a few mementos

from his endeavors, mementos that were as much a part of my own childhood as

they were of his fascinating career.

I

was told that Mr. Plimpton would be down shortly. Fifteen minutes later he

finally appeared. I hope my mouth didn’t hang open the way mouths hang open in

cartoons when a character sees something bizarre: George Plimpton was

unshaven, sloppily dressed in a wrinkled tee-shirt and baggy sweatpants, his

hair an unforgiving matrix of shapes, his eyes completely bloodshot. He seemed

entirely unfocused and didn’t dive into a conversation as much as wade into it

slowly, with what seemed to be uncertainty and maybe even regret. My first

thought was that he had accepted the assignment too fast, that he really didn’t

want to do it, and that his late arrival and gloomy appearance was his way of

telling me he wanted a way out.

But

then I had my second startling

realization: could it simply be that he was hung over? I had to believe that to

be true, for if anyone knew how to select the right words to find a way out of a

situation, it would be George Plimpton. And he didn’t seem intent on finding

those words. He have been drinking overnight.

So a man I had so admired was singlehandedly derailing my public relations career—and

thus my writing career—right before my eyes, which initially had been as wide

as his were red. How would this press conference turn out? The event was just a

week away. Would Mr. Plimpton completely misunderstand and misrepresent the

technical details of the camera? Would he show up at the wrong hotel? Would the

trade press write scathing articles about the ridiculous Olympus press

conference? Would I be laughed out of a job? Would I ever get another? And if

not, how would I support my family, especially since I had not yet written the

Great American Novel?

|

| George Plimpton |

The

day of the press conference arrived. I paced the ballroom floor like an

expectant father (which, if memory serves, I actually was at the time). George

showed up three minutes before he was scheduled to speak. And when he finally

did take the podium, he was dapper and eloquent. He told some marvelous stories

about the time he boxed with Archie Moore and played goalie for the Boston

Bruins. The press conference guests seemed engaged and amused. Mr. Plimpton was

the same confident professional amateur that he had been in those old TV

specials, and he concluded by flawlessly describing the Olympus professional

amateur camera the way it needed to be described. It seemed as if he had been

using the camera successfully for months, even though it had not yet been

officially introduced to the market.

Was

it a perfect press conference? No. I hadn’t supplied nearly enough slides to our audio-visual

technician to show on the screen behind Mr. Plimpton to accompany his oral presentation. I had but four or five. I was upset about that. In fact, a few moments after he left the podium, our guest speaker overheard me telling my

boss how I wanted to shoot myself for not digging up more slides to project on

the screen. Mr. Plimpton turned to me and gently asked me why I simply hadn’t requested that he bring

some of his own when I was at his apartment a few days before. He said he could

have brought along dozens. Then he turned back to my boss, with a sympathetic look on his face, as if to say, 'Don't be too hard on the young chap. He's doing his best.'

The End

The End

3. When Irving Got Mad. And Vice Versa.

Parody was recently back in the news. Music division.

Weird Al

Yankovic, for example, the harmless provocateur of “I Love Rocky Road,” “Eat It” and “Like a

Surgeon” fame, not long ago returned to the ABC show “Galavant” as a comical singing

monk in an episode entitled “The One True King (To Unite Them All).” And then

there’s Dr. Demento, the disc jockey who made a career of playing novelty songs

on the radio. He’s the subject of a theatrical documentary called “Under the Smogberry

Tree” that is expected to premier shortly. The only reason a discussion

of both gentlemen might be considered newsworthy is because parody songs themselves

almost never make news these days. Nothing

surprises us anymore. Or shocks us. Right now there happens to be a nasty fight

between Dr. Demento and the production team that shot the documentary footage

(the ongoing conflict has put the film in jeopardy, though the original

producers still insist it will debut soon). But even a battle like that pales

in comparison to some of the clashes that went on half a century ago.

|

| Irving Berlin |

Take March

23, 1964, for example. That’s when spinning cheeks into sheiks became legal. Or,

more accurately, it was when taking a song like the famous Irving Berlin tune

“Cheek to Cheek” and turning it into a parody called “Sheik to Sheik” did not

become illegal, as Berlin hoped it

would be. This was the result of a court battle known as Berlin et al. v. E. C.

Publications, which concluded that frigid March afternoon fifty-three years ago. The

case pitted the famous composer and several other notable songwriters against

Mad Magazine. Mad had taken 57 illustrious songs, parodied the lyrics, altered

most of the titles, and told readers to sing them “to the tune of” the famous

originals.

The tunesmiths

weren’t amused and sued the publisher, naming 25 of those songs in their

complaint. They sought $25 million in damages, based on one dollar per song for

each copy of the magazine that was sold. Mad won. Twice, in fact.

Irving

Berlin was my grandfather’s idol. Grandpa—Poppy Benny, as I had always called

him—was a songwriter and recording artist who, even though the work for which

he was known was decidedly un-Berlin-like, still considered the Tin Pan Alley

legend his greatest inspiration. But despite how much I enjoyed and admired

Poppy Benny, I’m glad his idol lost the court case to Mad.

My grandfather, who went by the

stage name Benny Bell, wrote and recorded several noted ditties, such as

“Everybody Wants My Fanny,” “Take a Ship For Yourself,” “My Janitor’s Can” and

one that was a hit twice in his lifetime and once in mine, “Shaving Cream.”

That’s the one that uses a reference to the white facial foam to disguise a

common four-letter expletive. It was a popular song in 1946 and, thanks to Dr.

Demento, made it onto the top 40 pop charts in 1975.

While it

was the irreverent ditties that gave him his greatest success, my grandfather

did write several love elegies, not unlike Berlin’s first hit ballad, “When I

Lost You,” written after the death of his wife Dorothy in 1912. Poppy Benny was

six-years-old at the time, but considered learning that song one of the turning

points of his young life. “When I Lost You,” and a ballad written by my

grandfather called “If You Promise to Be Mine,” were the first two songs that I

ever memorized; combined, they comprised the soundtrack of my childhood, as

both songs echoed almost continuously from my grandparents’ apartment whenever

my family drove to Brooklyn for a holiday, and from my house whenever my

grandparents came out to Long Island for a visit. Poppy Benny sang both songs

with equal pleasure. So did I.

While most of Berlin’s

compositions can be said to be clever, Poppy Benny’s—other than “If You Promise

to Be Mine”—were mostly just silly. He wanted to be as well-known for his droll

double-entendres as Berlin was for his narrative and musical dexterity. I

wonder now how Poppy Benny reacted to the lawsuit in 1964; I was only seven at

the time, and can no longer ask him about it because he passed away in 1999. His

love for Berlin is partially what prompted my search into the life of the man

who gave us “Cheek to Cheek,” and that search, in turn, is what led me to “Sheik

to Sheik.”

*

There were many song parodies

before the 1960s, by such practitioners as Stan Freberg, Spike Jones and Allan

Sherman, though most of them mimicked classical compositions or works in the

public domain, and some were entirely original pieces that used words and sound

effects to mock contemporary music or social conventions. Berlin v. Mad paved

the way for a more direct kind of musical parody—the kind that made Weird Al

Yankovic famous with his recipe of turning the Knack’s “My Sharona” into “My Bologna”

and Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust” into “Another One Rides the Bus.” Poppy

Benny probably could have done something similar, but it’s important to note that my grandfather was genuinely afraid

of lawsuits, having nearly gotten in trouble with the law back in the 1940s for

a few of his novelty records, some of which were considered obscene by the

authorities. Weird Al was co-billed several times on the same stage with my

grandfather shortly after the mid-70s “Shaving Cream” resurrection. That was

shortly before he became a superstar. But who knows; without the Berlin v. Mad legal

decision a half-century ago, Weird Al might have become just another wedding

band accordion player.

Irving Berlin’s

co-defendants (represented by their publishing companies) included such notables

as Jerome Kern, whose “The Last Time I Saw Paris” in Mad’s hands became “The

Last Time I Saw Maris,” Cole Porter, who’s “I Get a Kick Out of You” was turned

into “I Get a Kick-Back From You,” and Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein

II, whose “Hello, Young Lovers” was transformed into “Hello, Young Doctors.”

Despite the participation of so many eminent songwriters, Berlin received most of

the press, not just because his name was in the title of the complaint, but also

because he was arguably the most celebrated of the bunch. And although he lost,

it didn’t stop him from being regarded, then as now, as one of the most

important and prolific purveyors of American popular music in the 20th century.

After all, as Poppy Benny would have told you, Berlin was American popular music; he wrote one of the most recorded

holiday tunes of all time, “White Christmas,” as well as the song many people over

the years (including my grandfather) insisted should replace “The Star Spangled

Banner” as the nation’s official anthem, “God Bless America.”

Despite

Berlin's renown, it was obviously difficult for the man to hear people (from

the mountains to the prairies) singing the melody of “Easter Parade” but using

words that Miss America would loathe:

“Don’t wear that bikini

The one that’s teeny-weeny,

Your looks are not important

In the Beauty Parade.”

Or this “Cheek to Cheek” imitation:

“Heaven

I’m in heaven

And our earth with rich black oil just seems to leak,

And we always find the happiness we seek

When we’re talking dough together

Sheik to sheik.”

Or “Blue Skies” masquerading as a healthcare commercial:

“Blue Cross

Had me agree

To a new Blue Cross

Policy.

Blue Cross

Said I would be

Happy that Blue Cross

Covered me.”

These

parodies appeared in a 1961 edition of the Mad magazine called “The Fourth

Annual Edition of the Worse of Mad,” in a section called “Sing Along With Mad,”

and were devised by several editorial staff members and long-time contributors.

The tagline of the special section was “A collection of parody lyrics to 57 old

standards which reflect the idiotic world we live in today.”

The case

was argued twice, the first time in 1962 in U.S. District Court. That one was

heard by Judge Charles Metzner, who ruled in favor of Mad in all but two of the

twenty-five songs named in the suit. According to the decision, twenty-three

were distinct enough from the original songs to be considered safe from

copyright infringement. The two exceptions, both written by Berlin, were

“There’s No Business Like Show Business” and “Always,” which Mad called,

respectively, “There’s No Business Like No Business” and (without a change in

the title) “Always.” Both parodies were pronounced by the court as being too

close to the originals with regard to fundamental phrases. And because twenty-three

out of the twenty-five were deemed okay, the ruling amounted to a win for Mad,

with a mere slap on the wrist for the other two.

Berlin et

al requested a second trial at the Court of Appeals Second Circuit, where Judge

Irving R. Kaufman presided. Kaufman was the justice who, thirteen years

earlier, had sentenced Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to death for espionage. This

case was somewhat less consequential to national security—though serious in its

own way—and Kaufman, like Metzner before him, ruled in favor of Mad, but this

time for all twenty-five songs in the

complaint. What Kaufman said in his decision was that the plaintiffs neither

adequately proved that the parodies “caused substantial and irreparable damage”

nor that the public would “have had any difficulty in differentiating between

the works” of the original composers and the Mad men.

“The

disparities in theme, content and style between the original lyrics and the

alleged infringements could hardly be greater,” Kaufman wrote, adding that even

using a few direct words and mimicking the meter is permissible in order for

the effort to be a successful parody.

The

plaintiffs then appealed to the United States Supreme Court, but the high bench

refused to hear the case.

While they

were writing it, the Mad parodists were undoubtedly convinced that the lyrics

were different enough to avoid legal trouble, but apparently they also knew

that “the idiotic world we live in” might nonetheless throw some trouble their

way. Perhaps that’s why they printed this tongue-in-sheik warning in the

special section: “For Solo or Group Participation (followed by arrest).”

No one was

arrested, but the publishing company had to endure a legal case that between

the original filing and the final decision dragged on for more than two years.

“We just

continued doing our thing with no trepidation, but knew from the outcome of the

first trial that from then on we had better make the differences between the

originals and our parodies very clear,” recalls Nick Meglin, a writer and

artist who worked on some of the parodies. “There was just a slight anxiety

while it was all going on since so many laws and their interpretations are

often unpredictable. But we knew the defendants’ position was, well, stupid.

Plus, we knew our lawyer was as sharp as the First Amendment, so we didn’t fear

the worst.” Meglin, who contributed to the magazine for almost 30 years, now

teaches illustration in North Carolina.

What is

interesting to consider, he further notes, is that the parodies merely brought

free advertising and promotion to the original songs and, by extension, to the

talents and merits of the original songwriters.

Mad had

actually swum in these novelty waters prior to the “Sheik to Sheik” case. In

1960, a year before the Berlin lawsuit was filed, the magazine ran a spoof

called “My Fair Ad-Man” based on the stage musical “My Fair Lady,” which was

still playing to packed houses on Broadway. Mad, founded in 1952 as a comic

book by publisher William Gaines and writer/editor Harvey Kurtzman, was already

well-known for its parodies of other comic books, such as Archie (which they

called “Starchie”) and for lampooning just about every aspect of popular

culture.

When the 1962

and 1964 trials were over, Berlin found himself in a strange new place. In his 1996

Berlin biography, “As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin,” author

Laurence Bergreen suggests that the lawsuit, in addition to influencing the

publication of satire, also impacted Berlin’s vanity, which by most accounts

was quite vast.

“To his

way of thinking,” Bergreen writes, “there was no end to the ways that the

disrespectful editors of Mad magazine had offended him.” Besides printing

lyrics so closely resembling his without payment or permission, they had,

Berlin believed, “corrupted the value of his original songs.”

The

court’s decision, Bergreen adds, made the songwriter “seem quite the

curmudgeon.” What’s worse, he was professionally humiliated by Judge Kaufman

when the justice addressed the issue of meter in his written decision: “We

doubt that even so eminent a composer as plaintiff Irving Berlin should be

permitted to claim a property interest in iambic pentameter.”

It didn’t

help, of course, that Berlin’s career was all but over by then. But the lawsuit

really had little if anything to do with that. By the conclusion of the trial

he was 76 years old and had been writing songs professionally for 58 years. The

last motion picture with which he was involved was “There’s No Business Like

Show Business” in 1954, eight years before the first lawsuit was initiated, and

his last Broadway show, “Mr. President,” which debuted in 1962, was

unsuccessful. And though he wrote a few dozen more songs afterward, none of

them approached even a scintilla of the popularity of his earlier catalog.

Was the

outcome of Berlin et al. v. E. C. Publications a foregone conclusion? Did Mad

have to win? Some think not.

“I

certainly believe a different judge could have made a difference. After all, it

took two different judges to decide between all of the songs in the lawsuit,”

notes Devin Lucas, a filmmaker who is currently involved in producing a

documentary about Dr. Demento, who more than almost anyone else is responsible

for the success of Weird Al Yankovic—and for my grandfather’s resurrected

career in the 1970s. “It could very easily be that Mad lucked into a final

judge who got a personal chuckle from the parody lyrics.”

Bill

Freytag, a musicologist, record collector and expert on the big-band era,

agrees that Mad wasn’t necessary disposed to win in the Berlin case. Berlin, he

speculates, would have won handily had the case been fought in the first three

or four decades of the 1900s, which was when Berlin more or less ‘owned’

popular music.

“Had there

been a judge who stubbornly still lived in the past, there could have been a

different outcome,” Freytag says. “But that didn’t happen. What’s more, by the

time Mad got into the picture, the public had already heard Allan Sherman’s

lyrics parodying classical and public domain songs, and they enjoyed it. A lot!

Also, Mad didn’t make recordings for release, so in effect their ‘sung to the

tune of’ directive went on in the public’s head. Perhaps the judge realized

that the law couldn’t, or shouldn’t, control our minds.”

Yankovic does make recordings for release, which

is why he occupies a somewhat different place in the novelty song milieu. “I

still don’t know how he gets away with it,” admits Meglin, who is a friend of

the “Eat It” man. But Yankovic makes it a point to obtain permission first.

There have been times when permission was denied by some original artists, and

he’s had some disagreements or misunderstandings with others, but he has never

been sued.

By

contrast, Mad has been to court on more than one occasion, once in a suit

defending their use of Alfred E. Neuman as their mascot (an image that, in one

form or another, can be traced back to the 1890s; the plaintive lost the case).

As far as the Berlin affair is concerned, there haven’t been too many in-depth

histories written about it from the vantage point of those directly involved.

Most of the plaintiffs have since passed away (Berlin died in 1989 at age 101),

and while many of the defendants are still here, scattered around the county

raising hell in one way or another, few include the 52-year-old story of the

lawsuit in their ramblings, published or otherwise. The facts of the case are

easily found, but gossip, secrets, tangents, memories and anecdotes seem to be

in short supply. That’s a shame since there are probably many such anecdotes,

from the bizarre to the instructive, from the harebrained to the ironic.

For

instance, on one hand, Irving Berlin sued Mad for parodying his songs, and on

the other, he was known to write parodies of his own. In fact, there is wide

speculation that he once wrote parody lyrics to Cole Porter’s “You’re the Top”—and

Porter was one of his co-defendants in the Mad lawsuit. Talk about irony. Still,

you can’t be too mad at Irving; his contribution to American music withers any

personality flaws he may have had. From ballads to Broadway, from pomp to

patriotism, his songs dictate that he can only be sued for making it difficult

for other songwriters to have the same kind of timeless influence. Berlin’s

range—musically and lyrically—was broad. When he was 70-years-old he was still

thinking outside his own massive musical box, writing a song called “Israel” on

behalf of the still-relatively-new Israeli independence. (Israel was also

Berlin’s real first name.) My grandfather also wrote a song about the new

Jewish homeland, which he titled “Home Again in Israel.” It was one of his most

flavorful and elegant compositions. The thing is, Poppy Benny wrote “Home Again

in Israel” in 1950, and Berlin wrote “Israel” in 1958. My grandfather’s song

contains this verse:

“Home again in Israel

At last, no more need I roam,

My sacred land, oh beautiful Israel

You are now my home sweet home.”

A verse in the Berlin song, written eight years later, goes:

“Wandering,

Through with wandering,

Nevermore to roam

Today’s the day we sing and pray

And thank God that at last you’re home.”

Too bad both

gentlemen are gone. This would have made a fascinating lawsuit.

The End

The End

Did you see me on the Tony Awards last year?

That’s because I wasn’t there.

Actually, there was a time when I thought I might be on the show one day, back in my actor wannabe days. But the curtain drew on those days many years ago. In my defense, it had nothing to do with failing to make my mark on stage; I had decided halfway through my college career to become a writer instead. In terms of interests and passions, writing always won out—even though acting is what brought me out of my red-headed, freckle-faced shell when I was a teenager. When I started to act on the high school stage, I suddenly had a full, engaging social life where once there had been none at all.

So for my first two years of college I majored in drama. But when I realized that what I truly wanted to do was write about people, and not just impersonate them, I switched to journalism.

But that doesn’t mean that my adult life has been devoid of some theatrical drama. It has, and I’m happy about that, for I believe that real-life theatrics can only add to the contributions I make as a writer. There was that one time, though, where the drama was quite Shakespearean, and I’m still deciding whether or not it was a journalism-worthy experience—or just a sadly embarrassing one that I’d be better off to forget.

To set the scene, I must tell you that I played Romeo in high school. It wasn’t easy. I had to wear tights in front of kids who made fun of me even when I wore pants. The red hair and freckles didn’t help, regardless of the marvelous words I had to work with: “O heavy lightness, serious vanity, misshapen chaos of well-seeming forms...”

Juliet was played by a cute, dark-haired girl named Linda, and she and I got along well during rehearsals. If there was any realism at all to our love scenes—and I’d like to believe there was—it sprang from the fact that we treated each other with respect. After all, we were serious young students of the theater.

|

| From the high school yearbook: bottom right, rehearsing with Linda |

Linda and I lost touch shortly after we killed ourselves, but soon I met another girl, Bonnie, and she didn’t seem to mind a red headed, freckle faced Romeo, either. Before long, I proposed. Fortunately, our families weren’t at war, and we didn’t have to resort to putrid potions and pointy swords to prove our love for one another. We’ll soon celebrate our 35th anniversary.

Not long ago Bonnie had to take a diagnostic test at the hospital. The staff was very nice and personable. We met doctors and technologists who made us feel relaxed. It was around this time that my job as a corporate writer was eliminated and I was starting to build a career as a full-time freelancer. I was working at home, elated at the prospect of not having to wear a tie and not having to shave every day. I wrote well into the early morning hours, puffing on pencils and pumped up with day-old coffee. I felt like the starving artist I had always wanted to be (without actually having to starve to do it).

Not long ago Bonnie had to take a diagnostic test at the hospital. The staff was very nice and personable. We met doctors and technologists who made us feel relaxed. It was around this time that my job as a corporate writer was eliminated and I was starting to build a career as a full-time freelancer. I was working at home, elated at the prospect of not having to wear a tie and not having to shave every day. I wrote well into the early morning hours, puffing on pencils and pumped up with day-old coffee. I felt like the starving artist I had always wanted to be (without actually having to starve to do it).

When Bonnie and I returned to the hospital for a follow-up visit, I was exceedingly tired, my eyes mere slits, my nerves rankled. I wore my sloppy writer’s clothes. Wrinkled and torn. I was unshaven. For a moment I worried that hospital security would call the cops. Being bohemian is one thing; getting arrested for it is something else.

I fell asleep in the waiting room. Suddenly I was awakened by one of the doctors. She introduced herself with a personable smile. I felt bad that I wasn’t in a better state of mind to return the pleasantries. Despite this, the doctor seemed willing to engage in small talk, perhaps to ease my mind about the results of my wife’s diagnosis. But with no energy to respond, I simply kept quiet. The doctor went away.

Moments later, Bonnie came out.

“Did Linda say hi?” she said, smiling.

“Who?” I asked.

“The doctor—your Juliet from high school,” she exclaimed. “She came out to talk to you, didn’t she?”

Had I known it was Linda, I could have at least acted halfway normal. That’s assuming, of course, that I’m a decent actor. I suppose the jury will always be out on that. But is it something to write about, or just an episode best left on the cutting room floor?

You be the judge.

_______________________________________________

You be the judge.

_______________________________________________

5. Joe Franklin: Venerable. Inimitable. Flammable.

There were so many things

that I wanted to say the first time I met Joe Franklin, the television legend

who passed away in January 2015. It was 2007 when I asked if I could meet him to discuss a book

I was writing about an old vaudeville and Borsht Belt performer who had

appeared several times on his long-running program, “The Joe Franklin Show.” I needed to pick

Mr. Franklin's brain about the performer, and I also wanted to congratulate him on what was then his 65th year in show

business.

But

only one thought crossed my mind as soon as I stepped over the threshold of his

office door: the place was a powder keg waiting to explode.

Franklin Central, on West 43rd

Street in the heart of the Broadway theater district, was not so much an office

as it was a print-and-vinyl depository of 20th Century entertainment. There

were thousands upon thousands of magazines and books and programs from countless

concerts and plays, sheet music and photographs spanning eight decades, posters

that were probably worth thousands of dollars, records galore, overflowing folders

and more, all of it stacked from the floor to the ceiling, covering not just

every wall, but on the floor in rows going north and south and east and west

and probably a few other directions thrown in for good measure. It was a maze

made of showbiz history.

So awesome. So distinctive. So

flammable.

I didn’t know if I should be

impressed or alarmed. I mean, something as simple as an errant ash from the

cigarette of someone passing by in the hallway could do the trick, or a burst

light bulb from a lamp on his desk, or an overly aggressive space heater. Mr.

Franklin and I would be dead in a heartbeat. I was very worried about it during

my short visit.

On the other hand, he was an

81-year-old legend who achieved his fame and status because he knew what he was

doing. Who was I to tell him how to run his office? No dummy, he. From his

first professional job when he was still a teenager, working for Martin Block’s

“Make Believe Ballroom” radio program, to his own iconic TV show on WOR from

1962 to 1993, where he interviewed tens of thousands of guests, from the wildly

famous to the wacko fringe, Joe Franklin became an institution without even

trying too hard. That, of course, is not really true—he worked very hard; but his style was at once so

relaxed and spirited, so gracious and genial, so in awe of others while being

entirely self-possessed, that it seemed as if he strolled through his career

without ever breaking a sweat.

|

| Joe Franklin |

But all those interruptions, in

concert with the way Mr. Franklin spoke (a rapid-fire and occasionally

sputtering stream of consciousness), made me wonder if he’d come through on that

promise.

I left his office, thankful that my

initial inferno fears were unfounded, and a few months later I discovered that

my other fear was unfounded, too: he came through with the testimonial.

I’m glad his office never burned down. He’s been gone more than two years now, and there hasn’t been much news—at least not publicly—about what happened to the hundreds of thousands of items that I saw stacked in not-too-neat piles throughout the room. I’m sure proper arrangements were made. But since the legend’s not there anymore, I’m not really going to worry about it too much.

The End

I’m glad his office never burned down. He’s been gone more than two years now, and there hasn’t been much news—at least not publicly—about what happened to the hundreds of thousands of items that I saw stacked in not-too-neat piles throughout the room. I’m sure proper arrangements were made. But since the legend’s not there anymore, I’m not really going to worry about it too much.

The End

______________________________________________________________________

6. A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Marquee

I once wrote a play called “Assorted Nuts at

Passover, or, The Night I Felt Like I Became the Last Real Jew Left in America.”

It is loosely based on the crazy Passover Seders I used to attend at my

grandparents’ Sheepshead Bay apartment in Brooklyn back in the 1970s. They were

wildly nutty, as were most of the relatives who were always there. But I never

found a producer, production company or theater willing to take on the play. I

vaguely recall reading one thank-you-but-no-thank-you note that said “Oy,”

which I’m fairly certain was directed at its 27-syllable title. I had to wonder

how much a long title has to do with the success, failure, or very life of a

play.

So I did a little research—and I

think that the only decisive conclusion I drew is that there are no decisive conclusions

to draw.

In 1970, Paul Zindel’s “The Effect of Gamma

Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds” unfolded on a Broadway stage, and Clive

Barnes, then writing for the New York Times, used such words as “discouraging”

and “stupid” in his review—but I don’t feel bad for Mr. Zindel because of the

context in which those words were used: “It has, I must admit, one of the most

discouraging titles devised by man,” Barnes began, “… yet curiously enough you

realize at the end of the play that the title is valid—valid but stupid.” Jerry

Talmer of the New York Post, who considered Zindel’s play a powerful and

beautiful story, said it had a terrible title “which is far less terrible once

you’ve seen the play.” Lee Silver at the Daily News concurred, adding that “the

title seems zany, weird or even superficial—until you experience the play. Then

it becomes poignant and hopeful.” I can only hope for my own work to be called

discouraging and stupid one day; you never know when that can lead to poignant

and hopeful.

“Gamma

Rays,” with its full 15-syllable tongue-busting title, was awarded the Pulitzer

Prize for Drama, and also won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award as best

new play of the year.

But other

than my rudimentary research into the matter, there apparently have been no

studies about the correlation between long and short titles and long or short

runs on Broadway, Off-Broadway, or anywhere else. What is clear is that long titles have given some critics something

extra to criticize from time to time.

The truth is that a brief title takes as much

thought and imagination as a marathon one, and that the paths playwrights tread

in search of perfect titles are filled with numerous motives, including wit,

poetry, simplicity, desperation, and bluntness. It was bluntness that seems to

have been the motive behind Peter Weiss’s choice in 1964, when he broke every

long-title record with “The Persecution and Assassination of Marat as Performed

by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de

Sade.” That’s a 24-word, 42-syllable brute of a title. Mollie Panter-Downes,

writing in New York Magazine, called the production “a long, abstract and

difficult debate” about liberty and dictatorship that was nonetheless “a

dazzling theatrical experience.” (She was also among the first to report that

the title was condensed to “Marat/Sade” “by arguing Londoners, to save breath.”)

When “Marat/Sade” crossed the Atlantic, it won the New York Drama Critics’

Award for best foreign play of the 1965-66 season.

“Marat/Sade”

was by no means the first of the long-titled breed, but its length does give it

a special place in theater history. Three years before Weiss completed it, Time

magazine’s reviewer warned audiences that “The marquees of Broadway may soon

have to poke the New Jersey Palisades, for a new American playwright is about

to arrive, and his considerable ability is exceeded only by the length of his

titles.” If Arthur Kopit’s “Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma’s Hung You in the Closet

and I’m Feeling So Sad” poked the Palisades, Weiss’s, a few years later, must

have scaled the Delaware Water Gap.

A long

title can grab critical attention without critical success, no matter who

writes the play. Certainly, “Matrimonium: Overruled Passion, Poison and

Petrifaction” is not one of George Bernard Shaw’s best-known efforts. William

Saroyan’s 1975 farce, “Rebirth Celebration of the Human Race at Artie Zabala’s

Broadway Theater,” wasn’t well received, either.

“Rebirth

Celebration” was about a struggling Off-Broadway theater proprietor who needed

a good production to keep his theater alive. Saroyan poked fun at the state of

New York theater in the mid-1970s and audiences apparently took it personally.

Even a shorter title might not have helped.

But a

shorter title may have helped William

Gibson’s 1975 Christmas comedy, “Butterfingers Angel, Mary and Joseph, Herod

the Nut and the Slaughter of 12 Hit Carols in a Pear Tree.” Gibson, author of “The

Miracle Worker” and “Two for the Seesaw,” was perhaps trying to capture some of

the inventive lunacy of a contemporary production with a much shorter title, “Godspell,”

but may have frightened some people away with its unforgiving title.

(The play

was full of inventive lunacy: it takes place in Nazareth and Bethlehem in 1

B.C. and the characters talk about such things as diapers and vitamins. When

Joseph asks Mary when she’s expecting the child, she says, “I think around

Christmas.”)

In the

case of a 1980 drama, its long title brought playwright Edward Allan Baker a

comparison to one of the greatest American writers—although it was a somewhat

dubious comparison. In his favorable review of Baker’s “What’s So Beautiful

About a Sunset Over Prairie Avenue?” New Yorker critic Brendan Gill said,

“Surely (the title) hints at some not very deeply buried death wish on Mr.

Baker’s part in regard to our commercial theater. How can so many words

possibly be made to fit on a Broadway marquee? Let me abandon this point with

the gentle suggestion to Mr. Baker that if ‘Main Street’ was good enough for

Sinclair Lewis, ‘Prairie Avenue’ might well be good enough for him.”

Baker, who is

currently writing a book on how penning “Prairie Avenue” drastically changed his

life, says that the title was the result of two other titles that he merged at

a moment’s notice. He recalls how as a college student driving along I-95 in

Rhode Island, he was suddenly mesmerized by a gorgeous twilight behind The

Adult Correctional Institute in Cranston. (Baker was attending the University

of Rhode Island.) He scribbled on a pad, “What's so beautiful about a sunset

over a prison?’ simply as an idea with no real narrative meat behind it. Months

later, Baker was told by the chairperson of the theater department at his

school that if he wrote a play, the department would produce it. One afternoon, this same chairperson told him

that she had to put together a list of plays for their next season—and by the

end of the day needed a title of his as-of-yet unwritten play. Baker rifled

through his notes, came across his I-95 scribble, then noticed another

scribble—a different rough, meatless idea—on the same piece of paper: “The

Bride Of Prairie Avenue.” That’s how “What’s So Beautiful About a Sunset Over

Prairie Avenue” was born—as a title, not a play. At the time, Baker still

didn’t know what it would be about. (The completed play concerns a character’s

struggle to flee a Southern New England slum.)

“Titles of plays

are extremely important to me,” Baker shared with me. “I believe they have a

bearing on how a play is received. I’m not going to see a play titled, ‘The

Inside of His Head,’ which was the title before Arthur Miller settled on ‘Death

Of a Salesman,’ or ‘Poker Night,’ which Tennessee Williams used before ‘A

Streetcar Named Desire.’ I think a title has to stir the unconscious in the

same way a good poem does.”

I don’t

think that anyone truly knows whether devising the perfect title takes creative energy, sheer inspiration, or just

dumb luck. Whatever it is, it’s probably the playwright’s first or second idea

that wins out in the end. If a title does result from a first or second idea

and still happens to have a dozen or more syllables, sophisticated audiences

(and even many critics) usually prove they can deal with it. Fortunately,

though, first and second ideas generally do

produce much shorter titles.

So if I can get a producer to be

interested merely in considering a play about the screwy Seders of Sheepshead Bay, I’ll tell him that

I already wrote one, and that its title is “Oy.”

_______________________________

7. A Radio Flyer in an Empty Nest

These

things have been around for generations. I’m sure I had one as a kid. I don’t

remember it, though, probably because it was a pretty typical thing to have.

Every kid had one. Having a Radio Flyer red wagon didn’t exactly make you

special.

My

own children had one during the course of their entire collective childhood,

but they probably don’t remember it, either. All three shared the same Radio

Flyer red wagon, along with every other kid in the neighborhood, which is why

it didn’t make them special, either.

Why

just one for all three kids? It wasn’t that I was cheap. I wasn’t. And it

wasn’t because the kids were four years apart, which made it just a little

easier to pass down many toys and games without too much commotion. It was

because a Radio Flyer wagon lasted for years, even when used to its maximum

capacity season after season. There was just no reason to buy a new one; the one wagon we bought served dozens of

purposes flawlessly, giving each child plenty of opportunity to use it as a doll

and toy cart, a stagecoach (with me as the horse), a pet carrier, a thinking

station, a delivery truck to assist in setting up lemonade and flower stand

businesses on the corner... The little Radio Flyer never failed in its duties.

Anyway,

that’s why I bought just one to last three childhoods.

From

what I recall, it wasn’t even too expensive. I guess I could have bought three, had I been so inclined. But I wasn’t so

inclined. Besides, the company that made it probably didn’t need any more of my

money. Other than the cheaper and far less impressive plastic Fisher-Price

wagons, nobody else but Radio Flyer seemed to make them. Of course, I don’t

know if that was really true, and it probably wasn’t, but that was my

impression at the time, and my impression is what drove my decision. I thought

of Radio Flyer as a monopoly, and didn’t want to make the company more powerful

than they already were. But it hardly mattered; the one wagon I bought held up

just fine, no matter which child claimed primary ownership, or how many times

it slammed into a brick wall, or how many winters it was left outside.

|

| Celia in 1986 |

|

| Me in 2015 |

On

the other hand, I don’t recall ever seeing a little metal red wagon that wasn’t a Radio Flyer. So yesterday I decided

to embark on some research (using Bing), but stopped myself when I realized

that I didn’t care too much. The only thing I do care about is that the Radio Flyer that I bought for Celia (born

1983), passed to Kate (1987), and finally gave to Dan (1991), is now back with

me (1957), an empty nester in a new home in another state. Whatever joy it

provided the three of them, it’s giving me five times that much now. Do I

really want to find out anything about it that might tarnish my grown-up

pleasure of using the hell out of it now? I have no real interest in its

corporate pedigree, product history, quality standards, competition… All I care

about is that it’s my trusty little helper now.

The

nest may be empty, but the backyard is full—full of hills and corners and places

ripe for a little alfresco creativity. Now that I no longer have to drive

anyone to school, or rehearsal, or practice, and I don’t have to listen to

teachers justifying hours of homework or go to football games just to watch a

five-minute halftime show, I have much more time than ever before to conjure my

inner landscape architect. But since there’s no one to drive to school, there’s

no one around to help me carry or move things around in the backyard, either.

What’s more, once you have an empty nest, you begin to realize that you no

longer have the strength and endurance you had when the nest was full.

That’s

where the Radio Flyer comes in.

Over

the last four summers, that little guy has lugged perhaps a thousand gigantic

rocks that I’ve used to create rock walls and tree borders; hundreds of bags of

topsoil and mulch to fill up gardens, raised beds and big clay pots; dozens of

large slabs of cement that I dug up from an old pool path to use as a walkway

on either side of the patio; countless bricks that now edge that cement slab

walkway; and plenty of large shovels and rakes and hoes and clippers and other

landscaping tools. The little red Radio Flyer has also functioned as a carting

service for downed tree limbs, trimmed hedge and bush branches, and countless

bags of autumn leaves.

Don’t

get me wrong: it definitely shows its age; you can actually see a little bit of

the ground when you look down on it because of a

somewhat-larger-than-a-hairline crack in its metal surface. One look inside,

where the children used to sit, or where their potted flowers and lemonade

pitchers used to reside, and you realize you would never allow a child ever to

dwell there again. That’s because in addition to the crack, the Radio Flyer is

completely rusted and bent out of shape, with a few shards of metal protruding

here and there. The handle is bent like a broken arm. It seems as if it’s about

to give way. But I say that every summer, and every summer it soldiers on,

unimpeded by its abuse and advanced age. It still holds everything I dish out,

its wheels still turn, the handle still helps me navigate from the shed to the

walkway to the gardens to the raised bed. I have no clue if its resilience can

be attributed to the way it was made, to a favorable fluke of manufacturing, or

just to my own crazy mixture of stubbornness, willpower, and pride.

All

I know is that it makes me feel special.

* * *

_____________________________________

8. By the Way, We Even Called Him Satchmo

It

wouldn’t surprise me if my old friend Keith became President of the United

States. When I knew Keith in high school, 41 years ago, he was charismatic,

bright, extremely popular. He’s also black. Sound like any president you know?

Keith

came to my almost all-white school in a Long Island suburb from another

district. We weren’t the closest of buddies, but I considered him a good friend.

In fact, I looked up to him, literally (he was a foot taller than me), as well

as in every other way. We were in the concert band and marching band together.

He played the trumpet a lot better than I played the clarinet. My high school

had a highly-regarded music program, which may have been one of the reasons

that Keith was given the opportunity to transfer from his own school.

From

what I recall, there were no issues at my school whatsoever with respect to the

half-dozen black students who attended (the term African-American was not yet

in vogue), nor with students from the other racial groups who were represented

in the student body. Keith turned some of us on to a lifelong love of jazz; he

was an extremely funny guy who made us laugh because of the stunts he

pulled—like when he sat on the passenger side of his car and used his extremely

long arms and legs to make it appear as if no one was driving. (I’ll never get

that vision out of my head—nor do I want to.) Plus, he was a caring friend who

was always available to lend a hand. I don’t remember ever thinking about his

race or the color of his skin. It just never came up.

Barack

Obama was elected president almost eight years ago, and reelected without much

of a fight. People coast to coast can discuss the changes that have taken place

in our country to have made his election and reelection possible, and as of

this writing, we can also discuss the changes that may possibly lead to our

electing a woman or a Jew to the highest office in the land. No longer will it

be a total surprise. It can happen.

|

| From my high school yearbook |

Nor

would it be much of a surprise if Keith

occupied the Oval Office one day. After all, he had such a majestic presence

back then, I imagine it has only grown and developed even more in the four

decades since.

But

thinking back on those days also reminds me of a Keith-related story that

probably could never happen today—at

least not without a few heads rolling in its wake.

Our

marching band was scheduled to attend an event at another school in a

neighboring town. A bus was parked near the football field ready to drive us

there. I was one of the first on the bus and sat up front. A classmate named

Bob followed close behind and sat across from me. A few other students took

seats behind us. Then Keith strode aboard, his head nearly scraping the top of

the bus.

“Hey,

you—” Bob called out, a mock-officious tone to his voice and a playful smirk on