Welcome to "Hey, You Never Know," a blog that's as much about sharing my passions and reflections as it is about seeking new opportunities. Below (and on subsequent pages) are several features I wrote on spec for magazines, which never made it into print. Some of the original recipients did send me considerate and encouraging responses of which I'm proud. So instead of letting these features wallow in my Dammit Drawer, I thought I'd share a few. After all, I wrote them to be read.

_________________________

My Pandemic Path

I have always wanted to write books. When I was younger, I also wanted to act in movies. (Acting in the movie version of a book I wrote would be pure paradise!) Instead, for 30 years I’ve been editing employee newsletters. And acting like I enjoyed it.

For the past year, due to social distancing requirements sparked by the pandemic, I’ve been doing that exclusively from my home-office in Connecticut. In fact, since I've seen so few friends and family members, I do almost everything from my home-office, from mingling to gossiping. It's enough to drive you crazy.

The window in my office looks out onto a small parcel of trees that begins near the far end of my backyard, and extends several yards beyond. At the very least, the sight of it helps me make believe that I can be Bill Bryson writing “A Walk in the Woods.” Or better yet, Robert Redford actually walking in those woods.

With no commuting to do or social events to attend, I had much more free time over the last twelve months than I used to. So I decided to use that time to summon my inner Bryson-Redford and build my own walk in the woods—a 145-foot-long path through the mini-forest behind my house, which I could use for mental health breaks throughout the day to maintain my sanity. I'm sure my mind isn't the only one with which this pandemic has toyed. Dare I say it again: it's enough to drive you crazy.

Finally, strictly for fun, I rescued some of the old, small ceramic animal-musicians that used to be part of a collection (a hobby I relinquished fifteen years ago) and gave them a second life guarding a section of the path.

I started building it a year ago, and finished early last summer. Now that spring has arrived, I'm getting ready to spruce it up after the minor damage inflicted by the winter. So far, however, only five other people have walked on my Pandemic Path. Real trekkers would consider it a joke since it takes just 82 steps to hike the entire length. But to be honest, I really don’t care. The path gives me a sense of accomplishment. And yes, it has kept me well-balanced during this unprecedented time. At least I think it has. Maybe after work today, I’ll take a walk through my Pandemic Path to chat with those ceramic animal-musicians. Granted, they might be very tired, since I'm convinced that they stay up all night jamming. But still, I’d love to ask those little guys whether or not they think I’m still sane.

__________________________

Noted New York psychoanalyst Gibbs Williams, author of the new memoir, “Smack in the Middle: My Turbulent Time Treating Heroin Addicts at Odyssey House,” recently interviewed me for various websites and blogs about the burgeoning market for authors who choose to self-publish.

Gibbs: You edited my new book, “Smack in the Middle,” which, even though it was not self-published, still required your skills to make it as professional as possible. Your process intrigued me. But the word on the street is that you’ve been tearing your hair out because of some of the writing you’ve seen in a number of recent books that are self-published.

Joel: Which I guess explains why the street is suddenly so hairy. But yes, it’s an entirely new world with the ease of self-publishing and free platforms like Amazon Kindle.

Gibbs: And the fact that it’s so easy to publish these days bothers you. I can tell.

Joel: Of course you can tell. You’d be able to tell even if you were blindfolded with duct tape, had Play-Doh stuck in your ears, and were locked in a vaudeville trunk.

Gibbs: Well, thank you for that image. And for the nightmare I’ll have tonight. As long as you don’t have duct tape and Play-Doh, would you mind telling me why it bothers you so much?

Joel: It bothers me on two occasions. The first is when the author pretends that he or she is a legitimately published author by neglecting or refusing to say that the book in question is self-published. The second is when the author makes absolutely no attempt to at least try to ensure that the work is as well-crafted as it can be.

Gibbs: I assume that’s because such behavior is an affront to professional writers who practice and support the art and craft of writing and have paid their dues over the course of many years.

Joel: Beautifully put. Maybe I should interview you. Why am I even here?

Gibbs: You’re not here. You’re in a vaudeville trunk.

Joel: If only that were true… What I mean is that it’s tough to advocate for the power, value and effectiveness of good writing only to witness some of what I’ve witnessed. Which is why hiding in a trunk isn’t the worst idea in the world, Gibbs.

Gibbs: What are some of the things you’ve witnessed?

Joel: I used to belong to a business networking group. We met monthly. At every meeting, each participant would stand and make a self-introduction. It got silly after a while since it was usually the same people making the same introductions. There was one guy who self-published a book on how to improve business. He always said something like, “It is now in its third printing!” Yeah—because he paid to have it printed on three separate occasions. And then there are all the authors who pay vanity houses to publish their books but then write press releases for their local newspapers that make it seem as if they’re moments away from being a Simon & Schuster bestselling author.

Gibbs: Allow me to play devil’s advocate for a moment. Don’t vanity houses provide an outlet for those authors who are highly skilled and deserving, but for whom legitimate houses have been elusive simply as an effect of not being in the right place at the right time?

Joel: Absolutely. But too many vanity houses do not feel an obligation to make sure that the authors they take on are highly skilled and highly deserving. It’s strictly a business for them. They don’t seem to care about good writing as much as they do about signing on someone to their most-expensive publishing packages. There are a few things these presses should do. One, strongly—very strongly—promote the fact that professional editing can make even the flimsiest, most amateur writing seem respectable and commanding. Two, offer highly affordable professional editing services to their clients and provide the names of several reasonably-priced professional editors—

Gibbs: Like you?

Joel: I want it put on the record that you’re the one who inserted that plug, not me. I submitted to this interview because I’m a hell of a nice guy, not because I’m an aggressive self-promoter.

Gibbs: So noted.

Joel: And three, while I would never think of suggesting this be mandatory, I wish that vanity presses would decide to make it a matter of policy to print “This book is self-published” somewhere on the spine or on the copyright page.

Gibbs: In other words, not just anyone should be allowed to call themselves a professional author.

Joel: I have a friend who’s a real estate agent. A while back, when I was desperately trying to get a novel published, he told me to stop whining and just self-publish the damn thing. I said to him, that’s not what makes a professional author. If your neighbor sold his house on his own, can he call himself a professional real estate agent?

Gibbs: The answer would be no.

Joel: Right. A professional real estate agent has to study rules and regulations, pass a test, and abide by a series of standards. Why should professional writing be any different? Getting published by a legitimate house is the license. It shows that you have the skill, did the homework, and abide by the standards. Now, as we’ve already established, sometimes it just doesn’t happen, even for the best of us. But in those cases—when a skilled, worthy writer just can’t find an established publisher—there are other ways of working toward that license, including getting published in magazines and utilizing a professional editor. Once you get some legitimate reader comments and improve your skills from the experience, then you can call yourself a professional author.

Gibbs: You’ve reviewed many self-published books. Do your opinions come out of that experience?

Joel: It exacerbated the opinion I already held. I’ve been following the self-publishing industry for about fifteen years now. I felt this way from the start. But recently I signed on with a pay-for-your-review company and reviewed about fifteen books, the vast majority of which were self-published. The writing in many of them was simply awful. Even when the intentions are good—and they usually are—and even when the authors are fine people—and they usually are—poor writing makes me think that they don’t really care about writing, that they don’t care about their audience, and that they’re full of themselves. That’s what poor writing does. Misplaced modifiers, mixed tenses, passive language, improper punctuation… It all adds up to a bad reader experience.

Gibbs: Which I assume you pointed out in your reviews.

Gibbs: The honeymoon was over.

Joel: It was a nasty divorce. I don’t even have visitation rights. What’s wrong with suggesting to new authors that they could use professional editing? What’s wrong with telling readers that what they’re about to read is self-published? If the topic is of interest and the cover is attractive enough, people will read it regardless. And then, the authors themselves, by virtue of seeing how to improve their writing through professional editing, will get better. It’s a win-win.

Gibbs: But too much of the self-publishing industry now is a lose-lose.

Joel: In my opinion, yes. And it doesn’t have to be that way.

Gibbs: What do you plan to do about it?

Joel: Go into the street, get some of my hair back, look for more interviews like this one to do, spread the word, tell people that there are plenty of people out there who can edit their work so it appears professional, then go on another honeymoon, but don’t come home until it’s consecrated.

Gibbs: You mean consummated.

Joel: No. That would be a sexual reference, which is not my intention. I mean consecrated in terms of the art and passion for good writing being sacred, sanctified, hallowed... Besides, I don’t want to think about sex when I’m writing. And I really don’t want to write while I’m having sex.

Gibbs: I want it put on the record that you brought that up on your own. I had nothing to do with it.

Joel: So noted.

Gibbs: You’re a true professional, Joel. Thank you very much for your time.

A blog about my book editing services can be found at:

https://book-editing-by-joel.blogspot.com/2020/08/never-underestimate-power-of-good.html.

Dr. Williams is also the author of “Demystifying Meaningful Coincidences (Synchronicities),” “Attitude Shifting” and other books, all of which are available on Amazon.

What is it about four o’clock in the morning that appeals to lyricists? It must be evocative of... well... something! Does it allude to an empty house where you can be alone with the nutjob dream you had at three-fifty-five, just before you woke up? Or the kind of silence that turns up the volume on your state of mind, or even your state of existence? Or the kind of darkness that can mean either utter loneliness or complete freedom?

"Four a.m.” has be heard on quite a number of records and on several soundtracks through the years, brought to life by such vocalists as Judy Garland, Shirley Bassey, Paul Simon and Karen Carpenter. But the thing is, four a.m. isn’t four a.m. anymore. Today’s songwriter may have to find a brand new way to paint a picture of four a.m.

Use of the lyric actually goes back more than a hundred years, to 1914, when Irving Berlin wrote a song called “I Want to Go Back to Michigan (Down on the Farm).” In it he tells the story of a silent, dark-canopied dawn from someone’s past that was shattered by a noisy bird: “I miss the rooster,” Berlin wrote, “the one that used to wake me up at four a.m.” Happiness, and even anticipation, can almost be detected within the memory. The song was recorded by several artists, one of the most famous being Judy Garland for the 1948 film “Easter Parade.”

Sammy Cahn and Ron Anthony wrote a song called “It’s Always 4 A.M.” that was also recorded numerous times, perhaps most notably by Shirley Bassey in 1967: “It’s always 4 a.m. Your thoughts take wings but nothing brings that needed bit of slumber.” Sad—but it alludes to the fact that nothing—not even four a.m.—can stop us from at least trying to make some sense of an often senseless world.

Less than a decade later, Paul Simon penned “Still Crazy After all These Years,” which he included on his 1975 solo album of the same name. As befits his role as one of our most acclaimed musical poets, Simon described sheer desolation in just eleven words:“Four in the morning, crapped out, yawning, longing my life away.” It’s like watching an old movie on TV in the pre-dawn hours that, even though it’s very dated, still makes us realize that our own lives are boring by comparison. At the very least, Simon makes us feel that we’re not alone in our own miseries.

The following year, Richard Carpenter, John Bettis and Albert Hammond wrote a song called “I Need to Be in Love” which turned out to be Karen Carpenter’s favorite song in the entire Carpenter catalog. The semibiographical ballad, no doubt reflecting her overall mood, places the action in an empty house seemingly filled both with gloom and also a touch of faith: “So here I am with pockets full of good intentions, but none of them will comfort me tonight. I’m wide awake at four a.m. without a friend in sight. I’m hanging on a hope, but I’m alright.” Karen wasn’t all right—but that may partially be why she sang it so convincingly. The ballad makes us wish that she had had someone around who could really help her. (By the way, in 1979 Karen also recorded “Still Crazy After all These Years” for her ill-fated solo album.)

Melancholy songs, to be sure—and yet, oddly comforting, perhaps merely because they provide an emotional release of sorts, whether we hear them on iTunes or sing them ourselves. That’s the beauty of song. Musically, four a.m. has been a lovely thing.

But I’ve been getting up a few times at night lately (I’m 62!), sometimes at four a.m. on the nose, and I feel the beauty fading. As I search of the bathroom door I sometimes think of Judy, Shirley, Paul, Karen. That’s when I realize just how much things have changed.

No longer is the house in total darkness. Ever! Between the everlasting yellow LED clock on the microwave and the red one on the oven, the gray light that flashes at the bottom of my computer monitor and the green one on my printer, and the blinking blue light on my cell phone, there’s always some kind of visible radiant energy somewhere around to disallow complete obscurity, not to mention a few faint hums which, at four in the morning, can sound like sirens.

Nor can I turn on the television and hope for a mindless old black-and-white movie to put me back to sleep. At four a.m., Trump may already be tweeting, and CNN’s “Early Start” might tell me exactly what he tweeted, in real time. Sadly, knowing that the President of the United States is doing to the dignity of his office what I just did in the privacy of my bathroom makes me never want to sing again—particularly any song that refers to four a.m. It’s been ruined forever.

______________________

You can read some of my published pieces here. At the bottom of the next page you can find information on all my books. I also have a separate blog you can visit to read all about my novel, "Blowin' in the Wind."

______________________

The Littlest Apple. Or the Day I Said Something Really Bad to My Sixth Grade Teacher.

[This is a transcript from a storytelling event called Mouth Off in which I participated in early 2019 at the Mark Twain House & Museum.]

By the time I was in eighth grade in 1971, I had already figured out how not to be so shy or easily embarrassed, to the point where I was able to wear tights. Now, before you tell your own story about me, let me explain: it was a costume. I played Mr. Bumble in my junior high school production of the musical “Oliver.”

But that wasn’t the case two years earlier, in 1969, when I was in Mr. Klaus’s sixth grade class at Bowling Green Elementary School, in Westbury, Long Island. At that time I was exceedingly shy and very easily embarrassed. Of course, if what happened to me happened to you, you too might have been embarrassed, even if almost nothing could embarrass you.

I already had enough strikes against me, so I didn’t need anything unplanned or unexpected to add to what was a preexisting character trait. For one thing, I was one of only two or three Jewish kids in class, and things would sometimes happen like this: a classmate named Michael would come over to me and say, “Hey, Joel, can you say one of those funny Jewish words you learned in Hebrew School?” So I’d say the words for ‘Quiet, please,’ which is “Sheket, bevakashah,” and Michael would yell out, “Mr. Klaus! Mr. Klaus! Joel said a bad word! Joel said a curse!”

But Mr. Klaus had a knack for being able to put someone like Michael Iezzi in his place without throwing any attention on me. I appreciated that.

So there was that. Also, believe it or not, I was the only lefty in class, and whenever someone saw me writing they laughed because it looked like I was hugging a tree. I remember a girl named Betsy calling out, “Mr. Klaus! Mr. Klaus! Joel is writing an L that looks like a D!”

Again, Mr. Klaus took care of Betsy while leaving me out of it completely. That’s just one reason why I was happy to be in his class.

Also, I had red hair that was a lot redder than it is today, and freckles that were a lot frecklier than they are now. I went through first through fifth grades as the freckle-faced carrot-top strawberry orange kid, so being in Mr. Klaus’s class was a godsend. Besides being a great educator, he was a real kid-friendly guy. I felt lucky to have him as my sixth-grade teacher.

Mr. Klaus decided to have a holiday celebration, and his idea was to let every student be in charge of one thing for the party—cupcakes, drinks, balloons, board games—to sort of give everyone a little spotlight of their own. Everybody could use that from time to time. Especially me.

I had a terrific idea for my own little spotlight. My father was a technophile—the kind of guy who always had to be one of the first in the neighborhood with whatever new electronic gadget or gizmo was out at the time. We were one of the first on the block with a VCR, one of the first with cable TV, and in the mid-1960s the first with one of those little portable audiocassette recorders. It was a sleek-looking machine, and it sounded awesome. I thought that if I brought it in to provide music for the party, the other kids would think it was pretty cool—and no one would make fun of me for an entire day. So I asked Mr. Klaus if it was okay, and he said “Sure!” Just that one single-syllable word gave me an immediate dose of self-confidence. I couldn’t wait for the party.

The only problem was that we had just four music cassettes to go with it at the time—and they were all Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass. Now, here’s a case where 1969 was actually a little better than 1971: when I was in eighth grade, two rock ‘n roll bullies came over to me in the hallway and asked, “Hey, Samberg, what group do you listen to?” Bravely, honestly, and stupidly I answered, “The Carpenters,” and they laughed and shoved me into a locker.

But in 1969 it was perfectly fine to like Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass. They were cool. Plus, it was good party music.

So on the day of the party I brought in the cassette player and the four Herb Alpert cassettes. I began to play the first one, and the kids did think it was cool. Now, in those days, all the cassettes had only 30 minutes per side, so it wasn’t long before I had to turn it over to side B. Certainly that’s not the most complicated thing in the world. I mean, it’s not like landing a man on the moon (which happened the same year, incidentally). But I was a techno-klutz. I didn’t know if I’d end up pressing the wrong button or inadvertently pulling out the tape... I didn’t want to take the chance of anyone making fun of me, particularly since everything had been going so well.

It was a relatively simple problem with an equally simple solution. All I had to do was go into a corner of the classroom, bend down, figure it out, then go back to the party. So that’s just what I did. I went to the side of the class, just to the left of the door that leads into the hallway, crouched down, and turned the cassette over. Then, suddenly, the door swung open very fast. I was knocked over, dropped the cassette player, the tape ejected, the batteries popped out and rolled away—and I angled around toward the door and yelled “You idiot!”

It was Mr. Klaus who had opened the door.

I don’t think I have to tell you how I felt. You know. So did Mr. Klaus. I went to my desk and sat there for a while. Before long, Mr. Klaus sauntered on over. I don’t remember what he said verbatim (it was, after all, fifty years ago), but I remember the gist of it. It went something like this: “Look at this classroom, huh? Erasers on the floor, some shades up, some down, desks facing every which way... I guess some days are like that—when up seems down, left seems right, right seems wrong, yes seems no.... That’s okay, I guess. Some days are just crazy like that. Especially party days.”

He walked away, and I was as confused as I had ever been in my life.

But then came one of the final games of the day—bobbing for apples. Mr. Klaus told us to be careful, because in each apple he had hid a brand new shiny 1969 penny—expect for one apple, in which he hid a quarter! A quarter in those days could buy 25 Tootsie Rolls, which was my favorite chocolate treat. I could really use that quarter! I was eighth or ninth or tenth in line to dunk for an apple. I was sure someone would pick the quarter apple before me. When I finally got up to the big silver bucket filled with water, there were still a dozen or more apples inside. They were all regular, everyday, common, normal sized apples—expect for one, which was an itsy-bitsy, teeny-weenie little one. I looked at Mr. Klaus. He had a blank expression on his face and said nothing. But I heard him loud and clear.

Did I want to bob for that puny apple and risk having all the other kids make fun of me? An apple like that just makes no sense! On the other hand...

That’s the apple I picked. I don’t have to tell you what I found. You know. But what you don’t know, and what I don’t know, and what no one knows or can never know is whether or not it was that apple, that game, Herb Alpert, or anything else that happened that day that started to build in me whatever it was I needed to get to the point six years later when, in front of a gigantic auditorium filled with nasty high school kids I could once again wear tights without a stitch of shyness or embarrassment—but this time as Romeo in “Romeo and Juliet.” That’s right—a Jewish, left-handed, red-haired, freckle-faced, techno-klutz Romeo. It can happen, thanks to good teachers who could make you recognize that everyone makes a mistake once in a while, and it isn't the end of the world.

Speaking of Romeo, in the next set of stories (after you Click for Older Posts at the bottom left of this page) is a piece called "Misshapen Chaos" that shares another embarrassing incident, this time involving my one-time Juliet. Check it out, if you dare.

________________________________________________

It's One of the Most Famous Broadway Musicals of all Time. But You Probably Never Heard Of It.

In 1900, “Florodora” became Broadway’s first true blockbuster. Today, its name draws a blank even with the most conversant of musical theater lovers.

There has rarely been a lack of courage on Broadway. Over the decades the creative architects of theatrical innovation have tried almost anything, and the previous season, 2017-2018, was no exception. We saw the creatures of Bikini Bottom cut loose in “Spongebob Squarepants.” Then we were able to “Escape to Margaritaville” to learn about love and life on a tropical island the existed on the vibes of Jimmy Buffet songs. Then the animated classic “Frozen” tried to warm audiences. That was followed by an announcement of a new musical version of “King Kong.”

Will any of these new musicals end up a blockbuster? Can we turn to any musicals of the past century for guidance as to how long they may run or even be remembered? There’s really no way to tell. After all, on November 10, 1900, a British import called “Florodora” opened at Broadway’s Casino Theater that in many ways was the Great White Way’s first true blockbuster musical—yet hardly anyone knows about it today. So... who knows?

But despite several ‘firsts’ and newsworthy footnotes attributed to “Florodora” in 1900 and 1901, when the name of the show is uttered today it is met mostly with blank though curious stares, even from the most conversant of musical theater lovers.

Why was it so memorable and important at the beginning of the twentieth century? For one thing, it was the first show to enjoy as fervent a cult following as it proved to have during the initial run. This was due in great measure to its six beautiful chorines—dubbed the Florodora Girls—who stole hears and ovations like no chorus line before. For another, it was the first and perhaps only show to have so many cast members—again, the Florodora Girls—marry into great wealth. Also, it was regarded by many theater historians to have been the first Broadway musical to make a cast album (although scant physical evidence exists). And finally, it was the first Broadway musical to spawn more than a handful of hit songs—songs that were played countless times in phonograph parlors all over New York City and even in towns and cities well beyond. That was a remarkable feat since there was neither television nor radio at the time to promote the show or its score and to spread its popularity.

“Florodora” had a few other distinctions, as well, including the financial ills of some of its creators, several lawsuits involving show personnel, a terrible train accident in which road show cast and crew members were involved—and the infamous court case following the 1906 murder by Harry Thaw of famed architect Stanford White. Thaw, a mentally unstable millionaire coal and railroad heir, was married to the beautiful model Evelyn Nesbit, who became a Florodora Girl in 1901. Prior to the marriage, the teenage Nesbit had had a sexual liaison with White that was known to have been highly indecent, a fact that deeply troubled Thaw. While White was at a theater watching a show, Thaw walked up behind him and shot him in the head. He was found not guilty by reason of insanity.

With all those firsts and distinctions, why has “Florodora” more or less been lost to the ages? In its defense, not many of its contemporaries are easily brought to mind. Quite a number of musicals throughout the nineteenth century and in the first decade or two of the twentieth were bawdy comic operas which, by their styles and formats—with the exception of Gilbert & Sullivan—did not find much favor with subsequent generations. Of the other 19 musicals on Broadway at the time of “Florodora,” few were hits. “The Gay Lord Quex,” was called “one of the most uncompromisingly filthy plays ever seen in New York” by one of the newspaper reviewers. It lasted less than ten weeks. “A Royal Rogue,” about a ruthless social climbing narcissist who hated the imperial class, closed after a month. “A Million Dollars” was about a barber who suddenly finds wealth and embarks on a shopping spree, which apparently wasn’t as exciting as a barber who murders people, a story that came to Broadway 79 years later. Like “Florodora,” none of those other musicals from the turn of the century slip off today’s tongue very easily.

Speaking of murderous barbers, the plot of “Florodora” may not be as pungent as “Sweeney Todd, The Demon Barber of Fleet Street,” but it can be argued that it was unusual enough—some may say far-fetched enough—to have been at least a factor in its appeal to audiences in 1900 and 1901. The play is about the efforts of a beautiful woman named Delores to regain control of a Philippine tropical paradise called Florodora. The island had been usurped by an unscrupulous businessman named Gilfain, who plans to marry Delores and betroth all of his clerks to the island girls as a way to secure his hold on Florodora. But as luck would have it, Gilfain’s manager falls in love with Delores and his clerks fall in love with six visiting English darlings. These darlings are the famous Florodora Girls. In the end, everyone on Florodora ends up hitched—Gilfain to a penniless noblewoman!—and the island is finally returned to its rightful owner.

If one were to go by critical reaction alone, it would be hard to see why “Florodora” became as popular as it did. The New York Times said that “the lyrics are gracefully written and much of the music is unusually tuneful. But the singing is generally bad.” The libretto, the Times’ reviewer added, “is quite beneath contempt.” Wrote the New York Herald, “With much that was applauded, there were long wastes which tried the patience of the audience.” The New York Dramatic Mirror weighed in with the opinion that “There is something so pathetically English about ‘Florodora.’ There are parts of it almost too sad to write about.”

But as was proven to be the case, despite the bad singing, the ‘contemptuous’ libretto, and the perceived sadness, “Florodora” generated enough electricity to keep audiences flocking, men pining, and music companies cranking out cylinders and sheet music.

It may have mattered little how well the Florodora Girls sang or danced, but as far as the show’s creative team was concerned, it mattered very much how they looked and glowed. Each Florodora Girl was required to be 5’4” tall and weigh 130 pounds. Just how the team measured the sexual vibe during auditions is lost to history and all that remains is speculation. But somehow they did it. The result of that vibe? At least five of the original six Florodora Girls married into money after their “Florodora” debuts, and the sixth started out that way. Before being cast in the show, Marjorie Relyea had been married to a nephew of wealthy industrialist Andrew Carnegie. The nephew died on opening night when the play tried out in New Haven, and left Marjorie a fortune. After she departed the show, she married once again, this time to a rich stockbroker.

Florodora Girl Daisy Green also married a wealthy stockbroker. Agnes Wayburn was wooed by and then betrothed to a diamond magnate from South Africa. Vaughn Texsmith hooked a silk manufacturing titan. Another Florodora Girl, Marie Wilson, ditched her husband when “Florodora” opened and hitched her 5’4” wagon to a prosperous racehorse owner. She also fraternized with Wall Street insiders and independently earned three-quarters-of-a-million dollars. Finally, Margaret Walker also cleaned up on stock tips and soon married a millionaire. As rumor had it, she eventually entered into a long-term relationship with another well-to-do woman.

Throughout the run of the original production more than 70 women were part of the glamorous sextet.

Singing the praises of the Florodora Girls may have been an obsession of male theatergoers, but singing songs from the show became a habit of people far beyond the confines of the Casino Theater.

Phonograph machines were still practically nonexistent in American homes at the time, but between the neighborhood phonograph parlors (a penny a play) and sheet music sales, the distribution and sale of “Florodora” music was nearly an industry onto itself. Two songs from the score, “Tell Me, Pretty Maiden” and “The Shade of the Palm,” were among the most popular show tunes of the era. The Music Trade Review ran many articles in 1901 about the success of “Florodora” music; in one they talked about the Royal Music Company being so busy printing sheet music that “they have been kept at it from early morning to late at night.” The trade paper also reported that music stores from out of state (where hardly anyone had yet seen the show) were ordering exceedingly high numbers of “Florodora” sheet music. It was also documented that despite the infancy of the recording industry, almost 60 separate versions of “Florodora” music were recorded onto cylinders or discs. (There were only five companies at the time that made cylinders or discs.)

“At Graphophone Co. retail headquarters, people would come in to hear ‘Tell Me, Pretty Maiden’ over and over. Some play it five times in a row,” wrote Music Trade Review on July 30, 1901, when “Florodora” had been playing on Broadway for seven months. “One fluffy haired girl came in here one afternoon and spent ten cents in hearing the sextet ten times in succession.”

Had it not been for the popular songs and the alluring chorus girls, no one can know if “Florodora” would have been as popular as it was, for the only true star power it wielded to draw patrons to the Casino was in the person of actor Willie Edouin. England-born, Edouin had already been in show business for fifty years when he amused audiences in the London production of “Florodora” beginning in 1899. He played Gilfain’s flunky, a buffoon named Tweedlepunch, who had dozens of pieces of silly stage business to milk for laughs. One such bit was the character’s presumed skill at a form of phrenology (measuring a person’s capacities by the size and shape of their skull). Tweedlepunch was charged by Gilfain with looking at the heads of all the clerks on Florodora to determine who they should marry. Edouin, who was asked to reprise the role in New York, was best known for that kind of comic burlesque.

Had it not been for two brave novice American producers, Edouin may not ever have had the chance to bring Tweedlepunch to the Colonies. Leslie Stuart, who wrote most of the music and lyrics for the show, was once quoted as saying that when “Florodora” was playing in London, it was actually turned down by a prominent American theater manager who had been approached about taking it to Broadway. The manager allegedly said it was too English, too refined, and would be a flop in New York. But two other Americans, John Fisher, who owned a theater in California, and Tom Ryley, a comedian, neither of whom had ever produced a play before, traveled to England, saw the show, and offered to buy the American rights.

Once those rights were secured, a proper place to put on the show in New York became their next priority. That distinction was bestowed upon the Casino, which has a distinctive history of its own. In the latter part of the Nineteenth Century, Manhattan’s theater district was centered around 23rd Street. In the early 1880’s composer and music impresario Rudolph Aronson wanted to build a theater farther north, on the corner of Broadway and 39th Street. He commissioned distinguished architects Francis Kimball and Thomas Wisedell to design something that would magnetically draw people uptown. The result was the Moorish-style Casino Theatre, which had among its eye-catching appeal a terra cotta facade, circular corner tower, interior arches, arabesque patterns on the box-seat balconies, even a lush rooftop garden that often staged productions of its own.

The Casino Theater opened on October 21, 1882—before construction was entirely complete—with an operetta by Johann Strauss. There was a storm that night. The ceiling leaked. But this was not a harbinger of things to come; for next 18 years the Casino was home to a long line of successful light and comic operas. But its true historical reputation was cemented in 1900 when the Florodora Girls came to town. (The theater was taken over by the eminent Shubert Organization in 1905, the same year that it was heavily damaged by a fire. The theater survived the fire, but was torn down in 1930 and replaced by an office tower.)

Once the rights were acquired and theater selected, staffing the creative crew took center stage. Thirty-three-year-old George Lask, a notable stage director of the day, was brought in to mount the show. Arthur Weld was selected to conduct the orchestra. He was an eminent artiste who had been educated in some of the most prominent musical institutions in Europe.

Rehearsals began on October 16, 1900.

After a well-received out-of-town tryout at the Hyperion Theatre in New Haven, CT, “Florodora” settled in at the Casino.

Though London was still considered the theatrical capital of the world in 1900 and 1901, the lights were getting brighter on Broadway as an international showcase of live stage entertainment. After a vibrant life of more than a year and four months at the Casino (552 performances, which at the time was considered a very long run), “Florodora” had a few road company productions and professional revivals—but all that ended in 1920 (with the exception of a London revival in 2006). The show hasn’t been seen on an American stage since 1920, in an Atlantic City revival that eventually moved to Broadway and which had in its supporting cast a 12-year-old Milton Berle. Famed comedienne Fannie Brice starred in a 1920’s “Ziegfeld Follies” stage show called “I Was A Florodora Baby” (a portion of which she recreated in the 1928 movie “My Man”). With her trademark self-deprecating humor, Brice played a fictional Florodora Girl who did not marry into fortune. A 1930 movie called “The Florodora Girl” told the fictional story about the life of one of the show’s chorines, but otherwise had nothing to do with the fantastical tale told in the show.

The show’s composer, Leslie Stuart, began his career as a church organist, then became a music teacher, rehearsal pianist, and concert promoter. (Had he listened to his father, Stuart might have become a cabinet maker. But his love of music won out over his need to please the old man.) His earliest show compositions were for reviews and musicals in Manchester, Liverpool and elsewhere in England, and included “An Artist’s Model,” “The Circus Girl,” and “A Day in Paris.” “Florodora,” which debuted when he was thirty-six, was his first true sensation. His follow-up, “The Silver Slipper,” borrowed liberally from the “Florodora” mold and did well in England and New York.

In addition to composing, Stuart expended quite a bit of personal time and energy to fighting musical piracy and trying to improve copyright laws. He expended far less energy in adapting to the changing musical times or learning how to protect his financial interests. As a result, he faced bankruptcy and ceased having anything resembling a theatrical career by the time he was 45.

His co-creator, Owen Hall, whose real name was James Davis, also had a weak hold on finances. One contemporary journalist writing about Owen Hall said that he would have been much more insightful had he selected as his pseudonym Owing All. He was said to have had a sharp and critical tongue for anyone who criticized his work. But he did have a few successes after “Florodora” (several with Stuart), including “The Geisha,” “An Artist’s Model” and “The Silver Slipper.”

(While Stuart and Hall are generally given credit for the “Florodora” book and score, it must be noted that others contributed, including Ernest Boyd-Jones and Paul Rubens, who provided additional lyrics, and Frank Clement, who provided entire songs.)

In the end, like the show itself, there was little lasting fame for the composer and writer of “Florodora.” The same was true for the cast. Despite marrying into wealth, none of the Florodora Girls achieved any real measure of lasting fame on stage or screen, nor did any of the other actors from the original Broadway production. As for Willie Edouin, the most famous cast member at the time, he appeared in several other successful shows following “Florodora,” mostly in England and South Africa, but a few years later began to suffer a mental decline and passed away in 1908. Also, despite his long and varied career (one estimate puts the number of roles he played at 500), he lacked financial shrewdness and did not fare as well financially as his reputation may have indicated. “Florodora” was the highlight of his long career.

Several lawsuits followed in the wake of the show’s run. A Florodora Girl replacement was arrested for stealing rings, another sued a man for reneging on a financial promise, and one of the associate producers sued the show managers for withholding royalties. As if all that were not enough to cast a shadow on what had once been the brightest light on Broadway, in February 1902 a professional “Florodora” touring company on a train from Virginia to Delaware crashed into another train. The accident was blamed on heavy fog. Fire destroyed all the scenery, and ten cast and crew members were injured, one paralyzed from the waist down.

A “Florodora” curse of sorts? Hardly. Not with all those ‘firsts,’ all that early attention, and all those sheet music sales and phonograph parlor spins. If ever there was a Broadway musical that set a bar without becoming famous, it was “Florodora.” The truth is that even today no one can predict what will be a hit, what will flop, what will be remembered, and what will be mostly forgotten. Broadway success is not science. Lasting fame cannot be predicted. And as Tweedlepunch might tell us, we can’t even figure it all out by feeling the bumps on anyone’s head.

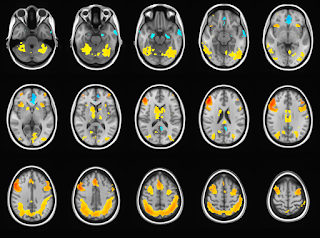

Not much beyond oxygenation and blood flow can be measured by an fMRI, rendering the technology’s further usefulness for something like a dream machine dubious at best.

Ian Wallace, an acclaimed Edinburgh-based psychologist who specializes in dreams, presents the same reasoning for his skepticism of a Dream Machine: the sheer number of neural connections involved in dreaming. His doubt stems not exclusively from a technological perspective, but also on the way he believes that dreams are generated by the brain in the first place. “The brain is almost more active during dreaming than it is in waking life,” he notes. The parts of the brain most likely involved in the formation of dreams, he reasons, have an incalculable number of places to look and search for signals. “I think there are more neural connections in the brain than there are stars in the known universe. Literally trillions of them. Trillions of combinations.” Right now, even IBM’s Watson would have a hard time dealing with that in any endeavor to find, record and play back dreams.

Shinji Nishimoto, who worked with Jack Gallant and now studies visual and cognitive processing of the brain at the Center for Information and Neural Networks (CiNET) in Osaka, offers further evidence of the infeasibility of tapping into dreams. “Given that we sometimes experience the same dream multiple times, there might be some neural mechanisms that induce the same (or similar) dreaming brain states,” he says. “Controlling such states, however, is beyond current technology.”

In some ways dreams are like movies: they are not real, but are based on elements of reality and possibly have a little internal direction, production design and editing thrown into the mix. It will likely surprise no one that movies come up often in any serious discussion of a Dream Machine. “All science fiction movies are inspiration for my research,” states Marvin Chun. James Fallon adds, “When I was a teenager I was into marine biology and other things, but then I saw ‘Charly.’ When I saw that, that put the hook in me. Watching that movie changed me.” That 1968 film, starring Cliff Robertson in an Academy Award-winning performance, was about an intellectually challenged man who undergoes experimental brain surgery that transforms him into a genius.

If it wasn’t a movie that attracted a researcher to this topic, chances are it was one of those beautiful landscapes.

And that’s probably a good thing.

|

| Mom as a young woman |

|

| Mom and her first great-granddaughter, Veronica |

|

| Mom & dad on their wedding day |

|

| Mom's journal |

|

| Mom and her five grandchildren |

|

| One of her journal doodles. A peek into her mind? |

|

| Doris Day even made an appearance in mom's journal! |

|

| Mom and dad at my daughter Celia's wedding |

The End

[Published magazine articles can be found here.]

Non-Skeletal Writer

The first time it was by a relative. (Even

more egregious that way!) He erroneously assumed that I was infringing on his business. (I

wasn’t.) The second time was when I was writing my book about Karen Carpenter,

“Some Kind of Lonely Clown,” and was warned by a supercilious interview source

that the Carpenter estate might sue me for such an ‘offensive’ title. (They didn't.)

The first time it was by a relative. (Even

more egregious that way!) He erroneously assumed that I was infringing on his business. (I

wasn’t.) The second time was when I was writing my book about Karen Carpenter,

“Some Kind of Lonely Clown,” and was warned by a supercilious interview source

that the Carpenter estate might sue me for such an ‘offensive’ title. (They didn't.) She happened to have been the niece of the grandson of one of my grandfather’s many cousins (seriously), whom I had met when I worked with him on a television show that the grandson was producing. His niece, the porn star, simply appreciated the fact that I regarded her as a long-lost relative instead of as a porn star. I don't think she was used to that.

She happened to have been the niece of the grandson of one of my grandfather’s many cousins (seriously), whom I had met when I worked with him on a television show that the grandson was producing. His niece, the porn star, simply appreciated the fact that I regarded her as a long-lost relative instead of as a porn star. I don't think she was used to that. No? None of that counts? Then I guess I’ll just continue doing what I'm doing and let whatever happens happen. If I have to keep writing things that upset some people, or if I have to keep on hugging porn stars, so be it.

Bye, Bye Baby. It's Cold Outside

This is not a post about the #MeToo movement. It’s about sense and sensibility. Not the book or the movie of that name, but the need for a little more of both when it comes to old songs, movies and plays.

As you’ve heard, there’s a call now (albeit not a very strong or successful one) to ban a famous 1944 song from the radio that tells the tale of a man who urges a woman to stay inside with him, where it’s a lot warmer than it is outside. Ostensibly his intention is to explore some carnal desires, even though the woman, through much of the narrative, says she really wants to leave. The song, of course, is “Baby, It’s Cold Outside,” by Frank Loesser, the famed lyricist and composer who also wrote the scores for “Guys and Dolls” and “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.” The song is written and performed as a slow-paced, chatty, good-natured tease about two people who, for all we know, may have been behaving like this together for years. But there are those who hear in its storyline something quite different, something quite nefarious, something for which the @MeToo movement was created. In some ways this is not dissimilar to calls to ban books like “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” not for #MeToo, but for racial insensitivity, or movies like “Monty Python’s Life of Brian” for blasphemy.

In my estimation, the number of times a lyricist, screenwriter, playwright or novelist had bad intentions or actually wanted to inspire disreputable behavior is astronomically small. Maybe one in a million. And for those one in a million cases, all we have to do is turn off the radio, throw out the book, skip the movie, or stay away from the theater.

If “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” is banned, then I suppose there are many movies, plays and even other songs that we should consider banning, as well. Here are a few examples, based on the following scenes, plot elements or lyrics:

• A comedienne faces an empty auditorium in a big theater and pretends to shoot every imaginary man, woman and child in the audience with a machine gun. Shouldn’t this overt suggestion of a mass murder raise an alarm with anyone who is bothered by our nation’s ineffective gun control legislation?

• A highly motivated but very impatient teacher shoves marbles into the mouth of a student who is having a hard time learning what he is trying to teach her. Is this not clearly cruel and inhuman punishment that can lead to asphyxiation and death?

• A gentle old man teaches young boys how to steal, and allows them to smoke and drink. With what we know about cults and amiable swindlers, should this not be troubling to anyone who cares about easily-influenced youngsters?

• A show business couple resorts to sneaking a powerful narcotic into the drink of a fellow entertainer in order to get their way in a business transaction. One could argue that this ‘entertainment’ teaches viewers to do whatever is necessary for success, regardless of the moral implications.

• A religious man helps a 13-year-old girl run away to make love to and marry an older teenage boy. Is that the kind of behavior we want our own children and grandchildren to emulate?

• A man hints to his girlfriend that he will have murderous intentions toward her if she decides to spend time with someone else. As bad as sexual harassment is—and it is very bad—is not threatening homicide and potentially carrying it out is even worse?

So when it comes to criticizing cultural gems of the past, let’s think about it calmly and logically before we do anything rash. After all, if we ban the plays, movies, and songs to which I refer above, we will never again be able to enjoy:

• “Funny Girl,” in which Barbra Streisand as Fanny Brice air-assassinates an entire theater;

• “My Fair Lady,” where Rex Harrison as Professor Higgins employs stringent methods to get Eliza to speak proper English;

• “Oliver,” which features the kindly Ron Moody as Fagin, who with song and dance merrily leads his band of puny pickpockets;

• “Bye, Bye Birdie,” where Dick Van Dyke and Janet Leigh slip a potion called Speed-Up into a conductor’s drink so that Conrad Birdie has more time to sing Albert’s song on TV;

• “Romeo and Juliet,” the Shakespearian classic which ends in tragedy, but not before the infatuated teens consummate their love with the help of Friar Lawrence;

• “Run for Your Life,” a 1965 Beatles song with the lyric “Well, I'd rather see you dead, little girl, than to be with another man.”

If I really wanted to, I could run around from town to town trying to get countless cultural examples of perceived moral decay banned from bookstores, library shelves and airwaves. But I’d rather enjoy the movies, plays and songs that I enjoyed as a child, all of which helped turn me into who I am today. To do that, all I have to stay home. But that’s fine with me because baby, it’s cold outside.

_________________________

860-321-7490, Joel@JoeltheWriter.com

Click Older Posts (below right) and you'll find the following articles:

1. Lebovitz and Warhol and a Case of Withering Sights

2. Pointing and Shooting in George Plimpton's Apartment

3. When Irving Got Mad. And Vice Versa.

4. Misshapen Chaos (my Juliet adventure)

5. Joe Franklin: Venerable. Inimitable. Flammable.

6. A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Marquee

7. A Radio Flyer in an Empty Nest

8. By the Way, We Even Called Him Satchmo

9. Love Between the Covers

10. The story of a water-breaking app

11. The non driverless car of the future

12. The best inning of a football game

13. Pot luck in Colorado